Data Science, Machine Learning, Natural Language Processing, Text Analysis, Recommendation Engine, R, Python

Monday, 30 September 2019

Amazon nearly doubled its revenue from its cloud and data biz India

How Artificial Intelligence Will Impact Filmmaking

Upscaling to Higher Resolutions

A recent example of artificial intelligence and its merger with cinema is the recent documentary Apollo’s New Moon, made by MagellanTV. In an interview with the director of the documentary, David Sky Brody, he explained how AI technology was used to create the film. Brody and his team enhanced original NASA film footage from Apollo mission moon landings to 4K resolutions. And they did it with AI-powered software. The process resulted in unprecedented, crystal clear images of the lunar surface. While some images for the film were already in large format (70mm), there were reels of raw analog video of the moon ...

Read More on Datafloq

Why Google Choose Dart & Not Any Other Language?

Well, to be exact, the whole hybrid mobile app development started back in 2011 when Xamarin decided to release its own solution i.e., Xamarin SDK (Software Development Kit) with C# for building hybrid mobile applications. Soon after, other companies decided to follow suit and that’s when Google launched the flutter framework to give some tough competition to the already existing market.

Now the question that comes into the minds of app developers is ‘why does flutter use dart?’ This question is already haunting a majority of mobile app developers who are skilled in programming languages other than Google’s Dart but wish to make use of the Flutter framework as well.

In this article, we will be providing you the top reasons why Google decided to choose Dart and not any other programming language for its Flutter Framework.

Reasons Google Chose Dart for Flutter Framework

In this ...

Read More on Datafloq

How Augmented Reality Is Transforming the Events Industry

From education to manufacturing and IT, you will be challenged to come up with one industry where augmented reality doesn’t offer a potential application. However, there’s one particularly exciting industry that offers unprecedented scope for both integrations of augmented reality as well as benefiting immensely from it. Say hello to the events industry. According to an international study, 87 percent of event planners have already organized an augmented reality-based event. 87 percent! Of course, numbers aren’t convincing enough on their own. So, we listed the most compelling collection of facts and benefits of AR in the events industry to help you realize what we are talking about.

1. ...

Read More on Datafloq

A Guide to Training Sessions at Spark + AI Summit, Europe

Education and the pursuit of knowledge are lifelong journeys: they never complete; there is always something new to learn; a new professional certification to add to your credit; a knowledge gap to fill.

Training at Spark + AI Summit, Europe is not only about becoming an Apache Spark expert. Nor is it only about being certified as Databricks Apache Spark developer, albeit both are imperative as part of your professional growth in today’s technical and data-centric economy.

It’s much more. You come to the summit to sharpen your big data skills—to learn how to build and architect end-to-end data lake pipelines from a myriad data sources; to build, manage, and productionize machine learning models; to explore patterns in big data using data science techniques; to immerse in deep learning frameworks such as TensorFlow and Keras—and how to code in them. All combined with Apache Spark, you go further in training to encompass related disciplines.

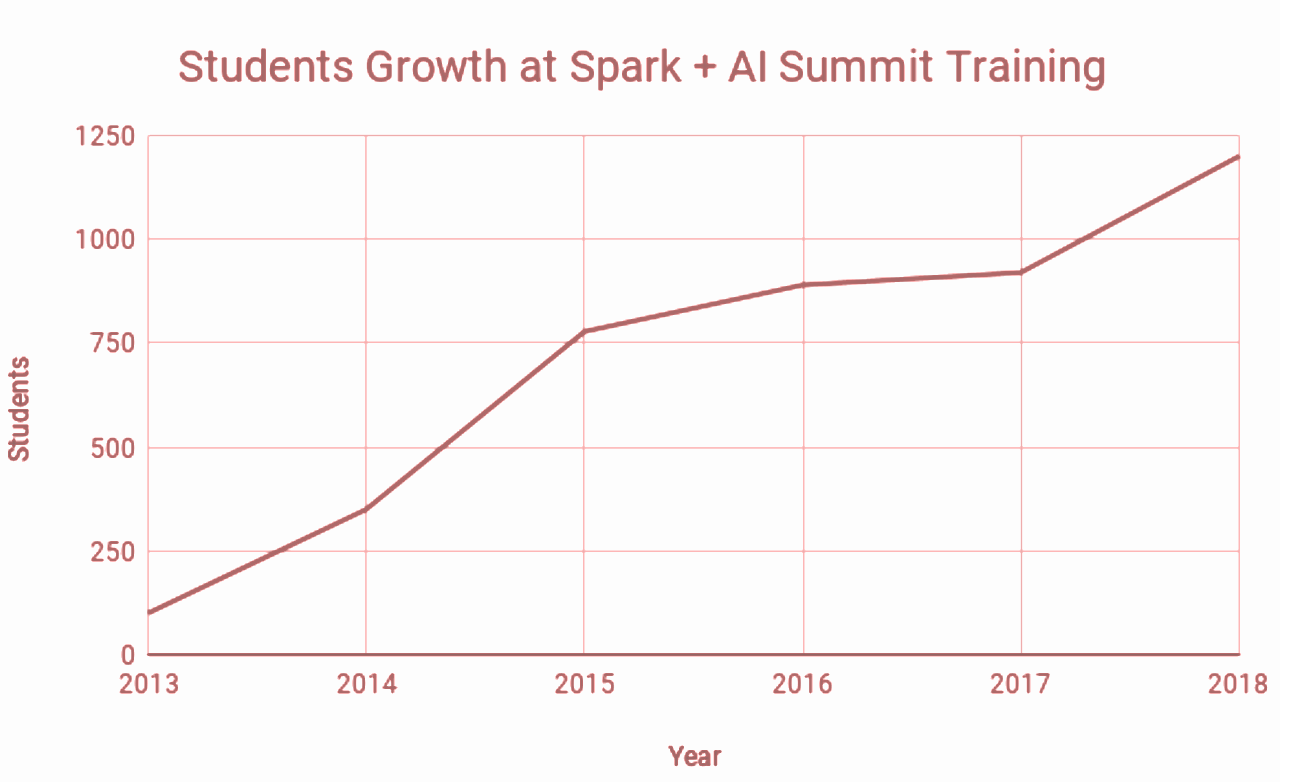

Since the early years of the summit, we have seen a sustained interest and increased participation by students in our courses.

To that end, we continue to offer several all-day training sessions taught by experts in their respective fields and supported by field practitioners as teaching assistants, including a half-day prep session for Databricks Apache Spark Developer Certifications.

Since its launch in early 2018, Databricks Certification has seen rapid growth, and by that year’s end, we had certified 266 engineers as Databricks Apache Spark developers. By August’s end this year, we certified an additional 242 engineers and saw YoY growth of 70%, from last year. With our new Certified Associated Engineer certification introduced this August, we certified an additional 42 applicants.

At the Spark + AI Summit, we are offering half-day preparation and examination course. Do check out other training courses for big data developers—all to extend your knowledge of Apache Spark and beyond. Here are a few training courses to select from:

- Apache Spark™ Programming

- Apache Spark™ Tuning and Best Practices

- Building Data Pipelines for Apache Spark™ with Delta Lake

- Machine Learning in Production: MLflow and Model Deployment

- Hands-on Deep Learning with Keras, Tensorflow, and Apache Spark™

- Data Science with Apache Spark™

- Databricks Apache Spark™ Certification and Preparation

Read More

Discover why big data professionals with knowledge of Apache Spark and machine learning are in high demand and the five reasons to become an expert.

Read who is giving what keynotes on the state of data and machine learning at Spark + AI Summit.

Find out which developer, technical deep-dives, and tutorials talks to select from at the Spark + AI Summit.

Attend sessions by machine learning practitioners on deep learning, data science, and AI use cases

Peruse the guide to MLflow Talks at the Spark + AI Summit

What’s Next

You can also peruse and pick community sessions from the full schedule. If you have not registered for the summit, use Jules20, a 20% discount code.

We hope to see you on Training Day in Amsterdam!

--

Try Databricks for free. Get started today.

The post A Guide to Training Sessions at Spark + AI Summit, Europe appeared first on Databricks.

Sunday, 29 September 2019

6 Tips For Speeding Up Data Analysis

That being said, perhaps even more important than analyzing data is the speed in which it can be done. In most cases, faster data analysis means more time to work on other areas. In the grand span of things, faster data analysis means greater success. With this in mind, let's go over six tips for speeding up data analysis.

#1: Have Regular Data Cleaning Sweeps

One of the first steps in having a faster data analysis process is cleaning it. To be more specific, running regular data clean sweeps is what allows for that. Now, depending on how much data is being swept, that process could take longer than normal. On the other hand, the ...

Read More on Datafloq

Friday, 27 September 2019

7 Blockchain Challenges to be Solved before Large-Scale Enterprise Adoption

Currently, many enterprises are experimenting with blockchain, but few have implemented a decentralised solution. According to a 2019 Deloitte report on enterprise blockchain adoption, 53% of the 1386 interviewed executives stated that blockchain had become a critical priority. However, only 23 per cent have actually initiated a blockchain deployment. While blockchain is gaining traction and acceptance in more industries, there are still some challenges left that need to be fixed first before we will see large-scale deployment. Let take a look a seven blockchain challenges that need to be fixed;

Seven Blockchain Challenges

1. Scalability

The first challenge is the technical scalability of blockchain, which is, at least for public blockchains, a hurdle that could limit their ...

Read More on Datafloq

Big Data Means Big Money: Why Businesses That Use Big Data Are More Profitable

In its simplest form, big data is a collection of information from many sources. This data is usually collected in one of three ways:

Asking users directly for permission to collect their information

Tracking software

Cookies that collect data on users as they browse the web

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that data on most of our actions are tracked, documented, and then used in a variety of ways. With this in mind, the potential for the exploitation of big data is a major concern, but the malicious usage of this information isn’t the norm. Rather, this information is used to better our lives.

Businesses stand to greatly benefit from big data. Today, business leaders and project managers know how to use big data in order to get the biggest return on investment. Streamlining operational inefficiencies, minimizing risk, getting a thorough look at business performance — the use of big data is valuable for all levels of management.

In our current economy, e-commerce, food tech, ...

Read More on Datafloq

Essential Data Science Job Skills Every Data Scientist Should Know

How do you distinguish a genuine data scientist from a dressed-up business analyst, BI, or other related roles?

Truth be told, the industry does not have a standard definition of a data scientist. You've probably heard jokes like “a data scientist is a data analyst living in Silicon Valley”. Just for fun, take a look at the cartoon below

Finding an “effective” data scientist is difficult. Finding people in the role of a data scientist can be equally difficult. Note the use of “effective” here. I use this word to highlight the fact that there could be people who might possess some of these data science skills yet may not be the best fit in a data science role. The irony is that even the people looking to hire data scientists might not fully understand data science. There are still some job advertisements in the market that describe a traditional data analyst and business analyst roles while labeling it a “Data Scientist” position.

Instead of giving a list of data science skills with bullet points, I will highlight the difference between some of the data-related roles.

Consider the following scenario:

Shop-Mart and Bulk-Mart are two competitors in the retail setting. Someone high ...

Read More on Datafloq

Biocon may cut Insulin rates to Rs 7 a day in select countries: Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

The Byzantine Generals Problem and AI Autonomous Cars

By Lance Eliot, the AI Trends Insider

[Ed. Note: For reader’s interested in Dr. Eliot’s ongoing business analyses about the advent of self-driving cars, see his online Forbes column: https://forbes.com/sites/lanceeliot/]

Let’s examine the topic of things that work only intermittently, which as you’ll soon see is a crucial topic for intelligently designing and building AI systems, especially for self-driving autonomous cars.

First, a story to illuminate the matter.

My flashlight was only working intermittently, so I shook it to get the bulb to shine, hoping to cast some steady light. One moment the flashlight had a nice strong beam and the next moment it was faded and not of much use. At times, the light emanating from the flashlight would go on-and-off or it would dip so close to being off that I would shake it vigorously and generally the light would momentarily revive.

We were hiking in the mountains as part of our Boy Scout troop’s wilderness-survival preparations and I was an adult Scoutmaster helping to make sure that none of the Scouts got hurt during the exercise. At this juncture, it was nearly midnight and the moon was providing just enough natural light that the Scouts could somewhat see the trail we were on. We had been instructed to not use flashlights since the purpose of this effort was to gauge readiness for surviving in the forests without having much in-hand other than the clothes on your back.

There were some parts of the trail that meandered rather close to a sheer cliff and I figured that adding some artificial light to the situation would be beneficial.

Yes, I was tending to violate the instructions about not using a flashlight, but I was also trying to abide by the even more important principle to make sure that none of the Scouts got injured or perished during this exercise.

Turns out that I had taken along an older flashlight that was at the bottom of my backpack and mainly there for emergency situations.

At camp, I had plenty of newer flashlights and had brought tons of batteries as part of my preparation for this trip.

While watching the Scouts as they trudged along the trail, I was mentally trying to figure out what might be wrong with the flashlight that I had been trying to use periodically during this hike.

Could it be that the batteries were running low?

If so, there wasn’t much that I could do about it now that I was out on the trek.

Or, it could be that the bulb and the internal flashlight mechanism were loose and at times disconnected, thus it would shift around as I was hiking on this rather bumpy and rutty trail. If a loose wire or connection was the problem, I could likely fix the flashlight right away, perhaps even doing so as we were in the midst of hiking.

Turns out we soon finished the hike and reached camp, and I opted to quickly replace the flashlight with one of my newer ones that worked like a charm.

Problem solved.

I’m guessing that you’ve probably had a similar circumstance with a flashlight, wherein sometimes it wants to work and sometimes not.

Of course, this kind of intermittent performance is not confined to flashlights.

Various mechanical contraptions can haunt us with intermittent performance, whether it might be a flashlight, a washing machine, a hair dryer, etc.

When I was younger, I had a rather beat-up older car that was in a bit of disrepair and it seemed to have one aspect or another that would go wrong without any provocation. One moment, the engine would start and it ran fine, while at other times the car refused to start and once underway might suddenly conk out. I had taken the ill-behaving beast to a car mechanic and his advice was simple, get rid of the old car and get a new one. That didn’t help my situation since at the time I could not afford a new car and was trying to do what I could to keep my existing car running as best as practical (with spit and bailing wire, as they say).

Let’s shift now to another topic, which you’ll see relates to this notion of things that work intermittently.

Valuable Lesson For Students

When I was a university professor, I used to have my computer science students undertake an in-class exercise that was surprising to them and unexpected for a computer science course.

Indeed, when I first tried the exercise, students would balk and complain that it was taking time away from focusing on learning about software development. I assured them that they would realize the value of the short effort if they just gave it a chance.

I’m happy to say that not only did the students later on indicate it was worth the half hour or so of class time, it became one of the more memorable exercises out of many of the computer science classes that they were required to take.

I would have each student pair-up with another student. It could be a fellow student that they already knew, or someone that they had not yet met in the class. Each pair would sit in a chair, facing each other across a table, and there was a barrier placed on the table that prevented them from seeing the surface of the table on the other side of the barrier.

I would give to each person a jigsaw puzzle containing about a dozen pieces.

The pieces of the jigsaw puzzle were rather irregular in shape and size. The pieces also had various colors. Thus, one piece of the jigsaw puzzle might be blue and a shape that was oval, while another piece might be red and was the shape of a rectangle.

One member of each respective pair would get the jigsaw puzzle already assembled and thus “solved” in terms of being put together.

The other person of the pair would get the jigsaw pieces in a bag and they were all loose and not assembled in any manner. The person with the assembled jigsaw puzzle was supposed to verbally instruct the other member of their pair to take out the pieces from the bag and assemble the puzzle. The rules included that you could not hold-up the pieces and show them to the other person, which prevented, for example the person with the fully assembled jigsaw puzzle of just holding it up for the other person to see it.

You were now faced with a situation of via verbal indications only, trying to get the other person to assemble the jigsaw puzzle.

This kind of exercise is often done in business schools and it is intended to highlight the nature of communications, social interaction, human behavior, and problem solving. There are plenty of lessons to be had, even though it is a rather quick and easy exercise. For anyone that hasn’t done this before, it usually makes a strong impression on them.

Since the computer science students were rather overconfident and felt that they could readily do such a simple exercise, they launched into the effort right away.

No need to first consider how to solve this problem and instead just start talking.

That’s what I anticipated they might do (I had purposely refrained from offering any tips or suggestions on how to proceed), and they fell right into the trap.

A student in a given pair might say to the other one, find the red piece and put it up toward the right as it will be the upper right corner piece for the puzzle. Now, take the blue piece and put it toward the lower left as it will be the lower left corner piece. And so on. This would be similar to solving any kind of jigsaw puzzle, often starting by finding the edges and putting those into place, and then once the edge or outline is completed you might work towards the middle area assembly.

This puzzle solving approach normally would be just fine. There was a twist or trick involved in this puzzle. The assembled puzzle was not necessarily the same as the disassembled one that the other person had. In some cases, the shape of the pieces was the same and went into the same positions of the assembled puzzle, but the colors the pieces were different. Or, the shapes were different, and the colors were the same.

Here’s what would happen when the students launched into the matter.

The person with the assembled puzzle would tell the other one to put the red piece in the upper right, but it turns out that the other person’s red piece didn’t go there and was intended to go say in the lower left corner position. Since neither of the pair could see the other person’s pieces, they would not have any immediate way of realizing that they were each playing with slightly different puzzle pieces.

When the person trying to assemble their puzzle was unable to do so, it would lead to frustration for them and the person trying to instruct them, each becoming quite exasperated. Banter was quite acrid at times. I told you to put the red piece in the upper right corner, didn’t you do as I told you? Yes, I put it there, but things aren’t working out and it doesn’t seem to go there. Well, I’m telling you that the red piece must go there. Etc.

Given that many of the computer science students were perfectionists, it made things even more frustrating for them and they were convinced that the other person was a complete dolt. The person with the disassembled pieces was sure that the other person was an idiot and could not properly explain how the puzzle was assembled. The person with the assembled pieces was sure that the other person trying to assemble the puzzle was refusing to follow instructions and was being obstinate and a jerk.

When I revealed the matter by lifting the barrier, there were some students that said the exercise was unfair. They had assumed that each of them was getting the same puzzle as the person on the other side of the barrier (I never stated this to be the case, though it certainly would seem “logical” to assume it). It was unfair, they loudly crowed, and insisted that the exercise was senseless and quite upsetting.

I asked how many of the students took the time at the start to walk through the nature of the pieces that they had in-hand.

None did so.

They all just jumped right away into trying to “solve the problem” of assembling the pieces. I pointed out that if they had begun by inspecting the pieces and talking with each other about what they had, it would have likely been a faster and more likely path of “solving the problem” than by just skipping straight into it.

What was interesting is that some of the students at times were sure during the exercise that the other student was purposely trying to be difficult and possibly even lying. If you told the other student to put the red piece in the upper right corner, you had no way to know for sure that they did so. They might say they did, but you couldn’t see it with your own eyes. As such, when the puzzle pieces weren’t fitting together, the person giving instructions began to suspect that the other person was lying about what they were doing.

There were some students that even thought that perhaps I had arranged with the member of the pair to intentionally lie during the exercise. It was as though I had somehow before class started been able to reach half of the class secretly and tell them to make things difficult during the puzzle exercise and lie to the other person. Amazingly, even pairs of friends thought the same thing. Quite a conspiracy theory!

For more about conspiracies, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/conspiracy-theories-about-ai-self-driving-cars/

Introducing The Byzantine Generals Problem

Tying this tale of the puzzle solving to my earlier story about the intermittent flashlight, the crux is that you might find yourself sometimes immersed into a system that has aspects that are not working as you imagined they would.

Is this because those other elements are purposefully doing so, or is it by happenstance?

In whatever manner it is occurring, what can you do to rectify the situation? Are you even ready in case a system that you are immersed into might suddenly begin to have such difficulties?

Welcome to the Byzantine Generals Problem.

First introduced in a 1982 paper that appeared in the Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems published by the esteemed Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), the article was aptly entitled “The Byzantine Generals Problem” — there are numerous variants of the now-classic problem and what to do about it.

It is a commonly described and taught problem in computer science classes and covers an important topic that anyone involved especially in real-time systems development should be aware of.

It has to do with fault-tolerance.

You might have a system that contains elements or sub-components that might at one point or another suffer a fault.

Upon having a fault, the element or sub-component might not make life so easy that the element or sub-component just outright fails and stops.

In a sense, if an element stops completely from working, you are in an “easier” diagnostic situation in that you can perhaps declare that element or sub-component “dead” and no longer usable, versus the more tortuous route of having an element or sub-component that kind of works but not entirely so.

What can be particularly trying is a situation of an element or sub-component that intermittently works.

In that case, you need to figure out how to handle something that might or might not work when you need it to work. If my flashlight had not worked at all, I would have assumed that the batteries were dead or that the wiring was bad, and I would not have toyed with the flashlight at all, figuring it was beyond hope. But, since the flashlight was nearly working, I was hopeful of trying to deal with the faults and see what could be done.

You could of course declare outright that any element or sub-component that falters is considered “dead” and therefore you will henceforth pretend that it is. In the case of my flashlight, due to the intermittent nature of it, I might have just put it back into my backpack and decide that it was not worth playing around with it. Sure, it did still kind of work, but I might decide to declare it dead and finished.

The downside there is that I’ve given up on something that still has some life to it, and therefore some practical value. Plus, there is an outside chance that it might opt to start working correctly, doing so all of the time and no longer be intermittent. And, there’s a chance that I might be able to play with it and get it to work properly, even if it won’t happen to do so of its own accord.

For the flashlight, I wasn’t sure what was the source of the underlying problem. Was it the batteries? Was it the wiring? Was it the bulb? This can be another difficulty associated with faults in a system. You might not know or readily be able to discern where the fault exists. You might know that overall the system isn’t working as intended, but the specific element or sub-component that is causing the trouble might be hidden or buried within lots of other elements or sub-components.

With my fussy car that I had when I was younger, if the engine wouldn’t start, I had no ready means of knowing where the fault was. I took in the car and the mechanic changed the starter. This seemed to help and the car ran for about a week. It then refused to start again. I took the car to the auto mechanic a second time and this time he changed the spark plugs. This helped for a few days. Unfortunately, infuriatingly, it stopped running again. Inch by inch, I was being tortured by elements of the car that would experience a fault (in this case, fatal faults rather than intermittent ones).

Intermingling Of Faults

One fault can at times intermingle with another fault.

This makes things doubly challenging.

It’s usually easiest (and often naive) to think that you can find “the one” element that is causing the difficulty and then deal with that element only.

In real life, it is often the case that you end-up with several elements or sub-components at fault. If the starter for my car is intermittently working, and also if my spark plugs are intermittently working, it can be dizzying and maddening since they might function or not function in a wide variety of combinatorial circumstances. Just when I think the problem is the starter, it works fine, and yet maybe then the car still won’t start. When I then think that the problem is the spark plugs, maybe it starts but then later it doesn’t due to the bad starter.

You can have what are considered “error avalanches” that cascade through a system and are due to one or more elements or sub-components that are suffering faults.

Remember too that a fault does not imply that the element or sub-component won’t work at all.

The faulty element can do its function in a half-baked way. If the batteries in the flashlight were low on energy, they were perhaps only able to provide enough of a charge to light the flashlight part of the time. They apparently weren’t completely depleted of their charge, since the flashlight was at least still partially able to light-up.

A fault can be even more inadvertently devious in that it might not function in a half-baked way and instead provide false or misleading aspects, not necessarily because it is purposely trying to lie to you. The students that were telling each other which piece to use for the puzzle were genuinely trying to express what to do. None of them were purposely trying to lie and get the other person confused. They were each being truthful as best they presumed in the circumstance.

I am not ruling out that an element or sub-component might intentionally lie, and merely emphasizing that the fault in an element or sub-component can cause it to lie, and this might be “lying” without such intent or indeed it might be that the element or sub-component is purposely lying.

A student in the puzzle exercise could have intentionally chosen to lie, which maybe the person might do to get the other person upset.

I’ve known some professors that tried this tactic as a variant to the puzzle solving problem, infusing the added complication of truth or lies detection into it. The professor would offer points to the students to purposely distort or “lie” about the puzzle assembly, and the other student needed to try and ferret out the truth versus what was a lie (you’ve perhaps seen something similar to Jimmy Fallon’s popular skits involving lying versus telling the truth with celebrities that he has on his nighttime talk show).

About Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) is the notion that you need to design a system to be able to contend with so-called Byzantine faults, which consists of faults that might or might not involve an element or sub-component entirely going dead (known as fail-stop), and for which the fault could allow that element or sub-component to still function but in a half-baked way, or it might do worse and actually “lie” or distort whatever it is supposed to do.

And, this can occur to any of the elements or sub-components, at any time, and intermittently, and can occur to only one element or sub-component at a time or might encompass multiple elements or sub-components that are each twinkling as to properly functioning.

Why is this known as the Byzantine Generals Problem?

In the original 1982 setup of this intriguing “thought experiment” problem, the researchers proposed that you might have military generals in the Byzantine army that are trying to take a city or fort. Suppose that the generals will need to coordinate their attack and will be coming at the city or fort from different angles. The timing of the attack has to be done just right. They need to attack at the same time to effectively win the battle.

We’ll pretend that the generals can only communicate a simplistic message that says either to attack or to retreat. If you were a general, you would wait to see what the other generals have to say. If they are saying to attack, you would presumably attack too. If they say to retreat, you would presumably retreat too. The generals are not able to directly communicate with each other (because they didn’t have cell phones in those days, ha!), and instead they use their respective lieutenants to pass messages among the generals.

You can likely guess that the generals are our elements or sub-components of a system, and we can consider the lieutenants to be elements too, though one way to treat the lieutenants in this allegory is as messengers rather than purely as traditional elements of the system. I don’t want to make this too messy and long here, so I’ll keep things simpler. One aspect though to keep in mind is that a fault might occur not just in the functional items of interest, but it might also occur in the communicating of their efforts. The starter in my car might work perfectly and it is only the wire that connects it to the rest of the engine that has the fault (it’s the messenger that is at fault). That kind of thing.

Suppose that one or more of the generals is a traitor. To undermine the attack, the traitorous general(s) might send an attack message to some of the generals and simultaneously send a retreat message to others. This could then induce some of the generals into attacking and yet they might not be sufficient in numbers to win and take the city or fort. Those generals attacking might get wiped out. The loyal generals would be considered non-faulty, and the traitorous generals would be considered “faults” in terms of how they are functioning.

There are all kinds of proposed solutions to dealing with the Byzantine Generals Problem.

You can mathematically describe the situation and then try to show a mathematical solution, along with providing handy rules-of-thumb about it. For example, depending upon how you describe and restrict the nature of the problem, you could say that in certain situations as long as only a third or less of the participants are traitors you can provide a method to deal with the traitorous acts (this comes from a mathematical formulation of n > 3t, wherein t is the number of traitors and n is the number of generals).

I use the Byzantine Generals Problem to bring up the broader notion of Byzantine Fault Tolerance, namely that anyone involved in the design and development of a real-time system needs to be planning for the emergence of faults within the real-time system, beyond just assuming they will encounter “dead” or fail-stop faults, and must design and develop the real-time system to cope with faults of an intermittent nature and faults that can at times tell the truth or lie.

Byzantine Generals Problem And AI Autonomous Cars

What does this have to do with AI self-driving autonomous cars?

At the Cybernetic AI Self-Driving Car Institute, we are developing AI software for self-driving cars. The AI for a self-driving car is a real-time system and has hundreds upon hundreds if not thousands of elements or sub-components. Some estimates suggest that the software for a self-driving car might amount to well over 250 million lines of code (though lines of code is a problematic metric).

The auto makers and tech firms crafting such complex real-time systems need to make sure they are properly taking into account the nature of Byzantine Fault Tolerance.

Bluntly, an AI self-driving car is a real-time system that involves life-or-death matters and must be able to contend with faults of a wide variety and that can happen at the worst of times. Keep in mind that an AI self-driving car could ram into a wall or crash into another car, any of which might happen because the AI system itself suffered an internal fault and the fault-tolerance was insufficient to safely keep the self-driving car from getting into a wreck.

For my article about the safety aspects of AI self-driving cars, see: https://aitrends.com/ai-insider/ai-boundaries-and-self-driving-cars-the-driving-controls-debate/

For another article of mine covering AI safety aspects, see: https://aitrends.com/ai-insider/reframing-ai-levels-for-self-driving-cars-bifurcation-of-autonomy/

I’d like to clarify and introduce the notion that there are varying levels of AI self-driving cars. The topmost level is considered Level 5. A Level 5 self-driving car is one that is being driven by the AI and there is no human driver involved. For the design of Level 5 self-driving cars, the automakers are even removing the gas pedal, the brake pedal, and steering wheel, since those are contraptions used by human drivers. The Level 5 self-driving car is not being driven by a human and nor is there an expectation that a human driver will be present in the self-driving car. It’s all on the shoulders of the AI to drive the car.

For self-driving cars less than a Level 5, there must be a human driver present in the car. The human driver is currently considered the responsible party for the acts of the car. The AI and the human driver are co-sharing the driving task. In spite of this co-sharing, the human is supposed to remain fully immersed into the driving task and be ready at all times to perform the driving task. I’ve repeatedly warned about the dangers of this co-sharing arrangement and predicted it will produce many untoward results.

For my overall framework about AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/framework-ai-self-driving-driverless-cars-big-picture/

For the levels of self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/richter-scale-levels-self-driving-cars/

For why AI Level 5 self-driving cars are like a moonshot, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/self-driving-car-mother-ai-projects-moonshot/

For the dangers of co-sharing the driving task, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/human-back-up-drivers-for-ai-self-driving-cars/

Let’s focus herein on the true Level 5 self-driving car. Much of the comments apply to the less than Level 5 self-driving cars too, but the fully autonomous AI self-driving car will receive the most attention in this discussion.

Here’s the usual steps involved in the AI driving task:

- Sensor data collection and interpretation

- Sensor fusion

- Virtual world model updating

- AI action planning

- Car controls command issuance

Another key aspect of AI self-driving cars is that they will be driving on our roadways in the midst of human driven cars too. There are some pundits of AI self-driving cars that continually refer to a utopian world in which there are only AI self-driving cars on public roads. Currently there are about 250+ million conventional cars in the United States alone, and those cars are not going to magically disappear or become true Level 5 AI self-driving cars overnight.

Indeed, the use of human driven cars will last for many years, likely many decades, and the advent of AI self-driving cars will occur while there are still human driven cars on the roads. This is a crucial point since this means that the AI of self-driving cars needs to be able to contend with not just other AI self-driving cars, but also contend with human driven cars. It is easy to envision a simplistic and rather unrealistic world in which all AI self-driving cars are politely interacting with each other and being civil about roadway interactions. That’s not what is going to be happening for the foreseeable future. AI self-driving cars and human driven cars will need to be able to cope with each other.

For my article about the grand convergence that has led us to this moment in time, see: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/grand-convergence-explains-rise-self-driving-cars/

See my article about the ethical dilemmas facing AI self-driving cars: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/ethically-ambiguous-self-driving-cars/

For potential regulations about AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/assessing-federal-regulations-self-driving-cars-house-bill-passed/

For my predictions about AI self-driving cars for the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/gen-z-and-the-fate-of-ai-self-driving-cars/

Dealing With Faults In AI Autonomous Car Systems

Returning to the Byzantine Fault Tolerance matter, let’s consider the various aspects of an AI self-driving car and how it needs to be designed and developed to contend with a myriad of potential faults.

Let’s start with the sensors.

An AI self-driving car has numerous sensors, including cameras, radar, ultrasonic, LIDAR, and other sensory devices. Any of those sensors can experience a fault. The fault might involve the sensor going “dead” and into a fault-stop state. Or, the fault might cause the sensor to report only partial data or only a partial interpretation of the data collected by the sensor. Worse still, the fault could encompass that the sensor is “lying” about the data or its interpretation of the data.

When I use the word “lying” it is not intended herein to imply necessarily that someone has been traitorous and gotten the sensor to purposely lie about what data it has or the interpretation of the data. I’m herein instead suggesting that the sensor might provide false data that doesn’t exist, or provide real data that has been changed to falsely represent the original data, or provided an interpretation of the data that maybe originally would have said one thing but instead gave something completely contrary. This could occur by happenstance due to the nature of the fault.

Those could also of course be purposeful and intentional “lies” in that suppose a nefarious person has hacked into the AI self-driving car and forced the sensors to internally tell falsehoods.

Or, maybe the bad-hat hacker has planted a computer virus that causes the sensors to tell falsehoods. The virus might not even be forcing the sensors to do so and instead be working as a man-in-the-middle attack that takes whatever the sensors report, blocks the messages, substitutes its own messages of a contrary nature, and sends them along. It could be that the AI self-driving car has been attacked by an outsider, or it could be that even an insider that aided the development of the AI self-driving car had implanted a virus that would at some future time become engaged.

For more about the computer security aspects, see my article: https://aitrends.com/ai-insider/ai-deep-learning-backdoor-security-holes-self-driving-cars-detection-prevention/

For the need to have resiliency, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/self-adapting-resiliency-for-ai-self-driving-cars/

For the potential of cryptojacking, see my article: https://aitrends.com/ai-insider/cryptojacking-and-ai-self-driving-cars/

Overall, the AI needs to protect itself from itself.

The AI developers should have considered beforehand the potential for faults occurring with the various elements and sub-components of the AI system. There should have been numerous checks-and-balances included within the AI system to try and detect the faults. Besides detecting the faults, there needs to be systematic ways in which the faults are then dealt with.

In the case of the sensors, pretend that one of the cameras is experiencing a fault. The camera is still partially functioning. It is not entirely “dead” or at a fail-stop status. The images are filled with noise and it makes the images occluded or confused looking. The internal system software that deals with this particular camera does not realize that the camera is having troubles. The troubles come and go, meaning that at one moment the camera is providing pristine and accurate images, while the next moment it does not.

We’ve previously let’s say put in place a Machine Learning (ML) component that has been trained to be able to detect pedestrians. After having scrutinized thousands and thousands of street scenes with pedestrians, the Machine Learning algorithm using an Artificial Neural Network has gotten pretty good at picking out the shape of a pedestrian in even crowded street scenes. It does so with a rather high reliability.

The Machine Learning component gets fed a lousy camera image that has been populated with lots of static and noise, due to the subtle fault in the camera. This has made the portion that has a pedestrian in it very hazy and fuzzy, and the ML is unable to detect a pedestrian to any significant probability. The ML reports this to the sensor fusion portion of the AI system.

We now have a situation wherein a pedestrian exists in the street ahead of us, but the interpretation of the camera scene has indicated that there is not a pedestrian there. Is the Machine Learning component lying? In this case, it has done its genuine job and concluded that there is not a pedestrian there. I suppose we would say it is not lying per se. If it had been implanted with a computer virus that caused it to intentionally ignore the presence of a pedestrian and misreport as such to the rest of the AI, we might then consider that to be a lie.

For more about Machine Learning and AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/machine-learning-benchmarks-and-ai-self-driving-cars/

For Federated Machine Learning, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/federated-machine-learning-for-ai-self-driving-cars/

For Ensemble Machine Learning, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/ensemble-machine-learning-for-ai-self-driving-cars/

For my article about the detection of pedestrians, see: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/avoiding-pedestrian-roadkill-self-driving-cars/

One should be asking why the system element that drives the camera has not yet detected that the camera has a fault? Furthermore, we might expect the ML element to be suspicious of images that have static and noise, though of course that could be happening a lot of the time in a more natural manner that has nothing to do with faults. Presumably, once the interpretation reaches the sensor fusion portion of the AI system, the sensor fusion will try to triangulate the accuracy and “honesty” of the interpretation by comparing to the other sensors, including other cameras, radar, LIDAR, and the like.

You could liken the various sensors to the generals in the Byzantine Generals Problem. The sensor fusion must try to ferret out which of the generals (the sensors) are being truthful and which are not, though it is not quite so straightforward as a simple attack versus retreat kind of message. Instead, the matter is much more complex involving where objects are in the surrounding area and whether those objects are near to the AI self-driving car, or whether they pose a threat to the self-driving car, or whether the self-driving car poses a threat to them. And so on.

The sensor fusion then reports to the virtual world model update component of the AI system. The virtual world model updater code would place a maker in the virtual world as to where the pedestrian is standing, though if the sensors misreported the presence of the pedestrian and the sensor fusion did not catch the fault, the virtual world model would now misrepresent the world around it. The AI action planner would then not realize a pedestrian is nearby.

The AI action planner might not issue car control commands to maneuver the car away from the pedestrian. The pedestrian might get run over by the AI self-driving car, all stemming from a subtle fault in a camera. This is a fault that had the AI system been better designed and constructed it should have been able to catch. There should have been other means established to deal with a potentially faulty sensor.

I had mentioned earlier to avoid falling into the mental trap of assuming that there will be just one fault at a time. Recall that my old car had the starter that seemed to come-and-go and also the spark plugs that were working intermittently, thus, there were really two items at fault, each of which reared its ugly head from time-to-time (though not necessarily at the same time).

Suppose a camera on an AI self-driving car experiences a subtle fault, which is intermittent. Imagine that the sensor fusion component of the AI software also has a fault, a subtle one, occurring from time-to-time. These two might arise completely separately of each other. They might also happen to arise at the same time. The AI system needs to be shaped in a manner that it can handle multiple faults from multiple elements, across the full range of elements and subcomponents, and for which those faults occur in subtle ways at varying times.

For ghosts that might appear, see my article: https://aitrends.com/ai-insider/ghosts-in-ai-self-driving-cars/

For the difficulty of debugging AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/ai-insider/debugging-of-ai-self-driving-cars/

For my article about the dangers of irreproducibility, see: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/irreproducibility-and-ai-self-driving-cars/

For the nature of uncertainty and probabilities in AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/probabilistic-reasoning-ai-self-driving-cars/

Conclusion

The tale of the Byzantine Generals Problem is helpful to serve as a reminder that modern day real-time systems need to be built with fault tolerance.

There are some AI developers that came from a university or research lab that might not have been particularly concerned with fault tolerance since they were devising experimental systems to explore new advances in AI.

When shifting such AI systems into everyday use, it is crucial that fault tolerance be baked into the very fabric of the AI system.

We are going to have the emergence of AI self-driving cars that will be on our streets and will be operating fully unattended by a human driver. We rightfully should expect that fault tolerance has been given a top priority for these real-time systems that are controlling multi-ton vehicles. Without proper and appropriate fault tolerance, the AI self-driving car you see coming down the street could go astray due to a subtle fault in some hidden area of the AI.

An error avalanche could allow the fault to cascade to a level that the AI self-driving car then gets into an untoward incident and human lives are jeopardized.

One of the greatest emperors of the Byzantines was Justinian I, and it is claimed that he had said that the safety of the state was the highest law.

For those AI developers involved in designing and building AI self-driving car systems, I hope that you will abide by Justinian’s advice and aim to ensure that you have dutifully included Byzantine Fault Tolerance or the equivalent thereof for aiming to have safety as the highest attention in your AI system.

Consider that an order by Roman Law, per the Codex Justinianus.

Copyright 2019 Dr. Lance Eliot

This content is originally posted on AI Trends.

AI Health Outcomes Challenge To Build on CMS Value-based Programs

By Deborah Borfitz

Giving Medicare beneficiaries control of their healthcare data and otherwise accelerating the adoption of value-based care are among the priorities of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), according to two CMS representatives speaking from the stage at the 2019 AI World Government conference in June. The agency believes patient data belongs to the patient and needs to be available at the point-of-care as individuals shop around for high-value providers—meaning it needs to be free flowing across the entire healthcare system.

Private-sector interest in the CMS Artificial Intelligence Health Outcomes Challenge, seeking ways to use AI to predict unplanned hospital and skilled nursing facility admissions and adverse events, has been particularly high with more than 300 qualified entries, reports Lisa Bari, who until recently was senior technical advisor for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Value-Based Transformation Initiative. The 20 participants selected for the first stage of the one-year competition will be announced in October, says a CMS spokesperson.

As publicly reported by CMS, Stage 1 participants will develop AI algorithms that predict health outcomes using Medicare fee-for-service claims data, as well as strategies for explaining the predictions to frontline clinicians and providers that would build trust in the data. Up to five participants will progress to Stage 2 and refine their solutions using additional Medicare claims data and up to $80,000 in monetary support.

All told, CMS and its partnering organizations could award as much as $1.6 million through the Challenge, most of it going to a single grand prize winner ($1 million) and the runner up ($250,000).

The CMS Innovation Center already provides data feedback to those testing innovative payment and service delivery models, per section 1115A of the Social Security Act, according to the CMS spokesperson. This AI Challenge will explore ways of enhancing that to drive interventions, such as care management and home visits, to improve quality and reduce the cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries.

“Value-based payment under the Trump Administration is the future,” the CMS spokesperson says. Recent changes to the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which encourages groups of healthcare providers to assemble into accountable care organizations (ACOs), are a “testament” to growing private-sector interest in pay-for-performance approaches.

Pathways to Success, launched last December, puts ACOs on a faster track to risk-taking while allowing the use of telehealth services and beneficiary incentive programs, the spokesperson says. Evidence is compounding that providers can deliver better results by taking on risk.

On the interoperability front, CMS is leading the way with Blue Button 2.0, says Director and CMS Chief Data Officer Allison Oelschlaeger. Blue Button 2.0 is an application programming interface (API) based on the open-source Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard and allows Medicare beneficiaries to authorize access to their claims data via a universe of 30 connected apps.

Beneficiaries can choose from a menu of apps designed to help them manage and improve their health by, for example, organizing their medical information and claims and selecting the best health plan for them, according to the CMS spokesperson. Beneficiaries can also choose apps that allow them to donate their data to clinical trials and research studies. Over 2,300 developers are now working in the Blue Button sandbox, using synthetic data to develop new apps.

Blue Button is one of the key projects under the MyHealthEData initiative being led by the White House Office of American Innovation, according to the CMS spokesperson. Its goal is to empower patients by giving them control of their healthcare data and allowing it to follow them through their care journey. CMS is now proposing that insurers in Medicaid, Medicare and the Health Insurance Exchanges likewise share claims data with patients.

Recognizing that care providers also need data to understand their patients better, CMS in July announced a “Data at the Point of Care” pilot that will allow providers to get a claims history on their patients via a FHIR-based API. Clinicians will be able to review medications, visits and previous testing. More than 500 organizations, representing over 50,000 providers, have expressed interest in this pilot, according to the CMS spokesperson.

Learn more at CMS Artificial Intelligence Health Outcomes Challenge and at CMS Blue Button 2.0.

Get Paid for Your Data, Reap the Data Dividend

By AI Trends Staff

AI algorithms typically required thousands or millions of data points to work effectively, increasing the value of data. But thanks to GDPR and similar efforts, the days of grabbing data from individuals without explicitly getting permission is numbered. The pendulum seems to be swinging the other way, toward avenues for granting clear permission.

One model for this is being offered by Oasis Labs, founded by Dawn Song, a professor at the University of California-Berkeley, to create a secure way for patients to share their data with researchers. Participating patients get paid when their data is used; participating researchers never see the data, even when it is used to train AI, according to an account in Wired.

Government is getting in the mix too. US Senator Mark Warner (D-Virginia) has introduced a bill that would require firms to put a value on the personal data of each user. The idea is that companies should pay to use personal data.

Health research is a good place to explore these ideas, says Song, because people often agree to participate in clinical studies and get paid for it. “We can help users to maintain control of their data and at the same time to enable data to be utilized in a privacy preserving way for machine learning models,” she said.

Song and her research partner Robert Chang, a Stanford ophthalmologist, recently started a trial system called Kara, which uses a technique known as differential privacy. In this model, the data for training an AI system comes together with limited visibility to all parties involved. The medical data is encrypted, anonymized, and stored in the Oasis platform, which is blockchain-based.

Silicon Valley incumbent giants such as Facebook and Google have built business models based on fuzzy permissions around use of data by their users. James Zou, a professor of biomedical data science at Stanford, sees a gap between permissions such as expressed in Sen. Warner’s bill and those granted in practice.

“There is a gap between the policy community and the technical community on what exactly it means to value data,” he says. “We’re trying to inject more rigor into these policy decisions,” he said.

Gov. Newsom of California Proposes Data Dividend

California Governor Gavin Newsome gave the idea of paying consumers for their data a boost in February, when he proposed a bill.

People give massive amounts of their personal data to companies for free every day. Some economists, academics and activists think they should be paid for their contributions.

“California’s consumers should… be able to share in the wealth that is created from their data. And so I’ve asked my team to develop a proposal for a new data dividend for Californians, because we recognize that your data has value and it belongs to you,” said Newsom during his annual State of the State speech, as quoted in CNN/FoxNews.

The idea is based on a model in Alaska where residents receive payments for their share of the state’s oil-royalties fund dividend each fall. The payouts vary from hundreds of dollars to a couple of thousand dollars per person.

It’s becoming more clear that as AI systems are being trained, they need data from wherever possible to get it: online purchases, credit card transactions, social media posts, shared smartphone location data, to name a few.

“There’s tremendous economic value that’s collectively created,” said Chris Benner, director of UC Santa Cruz’s Institute for Social Transformation. “All the data we generate every time we interact on any kind of digital platform is monetized.”

Recognizing the heightened awareness of the value of data, in June Facebook announced a market research program called Study, that aims to compensate willing users of Android operating system about their smartphone app use.

Users are to be paid a flat monthly rate through their connected PayPal account, according to a report in MarketWatch. Facebook would not provide an estimate of how much money users could be expected to make.

The app will collect information on what apps are installed on the phone, how much time is spent using those apps, the participant’s country, network type and device, and possibly what app features participants use. The data captured from the program, Facebook said, would help the company “learn which apps people value and how they’re used.”

Given its recent history in the exploitation of its users data, Facebook would have been well advised to have an independent review board evaluate the Study program for its ethical and legal implications, suggested Pam Dixon, the executive director of the World Privacy Forum. “We need more transparency from Facebook, and they have to go extra miles to prove that we can trust them because of their track record now,” she said.

Facebook said in announcing Study that it would not collect information like usernames or passwords, or photo and message content, and it would not sell Study app information to third parties or use it for targeted ads. The company said it would inform users of what information they would be sharing and how it would be used, before providing any data.

Read the original posts in Wired, CNN/FoxNews and in MarketWatch.

Announcing the First AI World Hackathon

Hackers get ready! Next month the AI World Conference & Expo will host its first hackathon on October 23-25 in Boston as part of AI World.

The AI Data Science Hackathon will bring together innovative data scientists and developers from across the ecosystem to solve real-world data challenges in applying artificial intelligence and machine learning. Working in teams, participants will build and improve on pipelines, datasets, tools, and other projects from fintech, insurance, healthcare, pharma, and more.

Participation is free, but space is limited, and interested teams and individuals are invited to apply as soon as possible.

Application is simple. Interested individuals or groups can briefly outline their project or area of interest via the online form and explain why it’s important to the community. Projects can be data sets, pipelines, applications, or algorithms which our diverse teams will work on throughout the hackathon with the goal of addressing real world data challenges in applying AI and machine learning.

Complete teams can register together under a Team Leader, or individuals or small groups can be joined with teams on site based on areas of interest, experience, and relevant skills. Hackathon mentors will be onsite to help groups plan their approach.

At the end of the Hackathon, teams will report on their progress and next steps to the whole community.

For more information, visit https://aiworld.com/hackathon.

Explainable AI is the Mission of Mark Stefik of PARC

As artificial intelligence (AI) systems play bigger parts in our lives, people are asking whether they can be trusted. According to Mark Stefik, this concern stems from the fact that most AI systems are not designed to explain themselves.

“The basic problem is that AIs learn on their own and cannot explain what they do. When bad things happen and people ask about an AI’s decisions, they are not comfortable with this lack of transparency,” says Stefik, Lead of Explainable AI, at PARC, a Xerox company. “We don’t know when we can trust them.”

“Existing theories of explanation are quite rudimentary,” Stefik explains. “In DARPA’s eXplainable AI (XAI) program and other places, researchers are studying AIs and explanation. This research is changing how we think about machine learning and how AIs can work in society. We want AIs that can build common ground with people and communicate about what they are doing and what they have learned.”

On behalf of AI Trends, Kaitlyn Barago spoke with Stefik about performance breakthrough as it applies to AI, the challenges these breakthroughs have led to in the scientific community, and where he sees the greatest potential for AI development in the next five to ten years.

Editor’s Note: Barago is an Associate Conference Producer for the AI World Conference & Expo held in Boston, October 23-25. Stefik will be speaking on the Cutting Edge AI Research program. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

AI Trends: Mark, how would you define the term “performance breakthrough” as it applies to AI?

Mark Stefik: A breakthrough in AI means the same as a breakthrough in anything else. It refers to a new capability that surprises us by being much better than what came before. Over the last decade or so, there have been breakthroughs in deep learning. This has led to AI approaches that can solve difficult problems better than any previous approach. Many people have heard of the upset victories by AIs in gaming situations such as in chess and by the AlphaGo systems. There have also been breakthroughs in image and activity recognition by computer vision systems, and progress in self-driving cars.

What are some of the challenges that these new breakthroughs have led to in the scientific community?

The biggest challenge is that computers weren’t designed to explain what they do; they were designed to find solutions. However, what they have learned and where they may fail remains opaque.

Most of the breakthroughs in machine learning date back to mathematical breakthroughs from the late ‘80s. It was discovered that given enough data, the neural networks of AI can fit complex curves to data gathered from many situations. The AI uses these curves to decide what to do.

For example, consider the problem of analyzing a photograph and deciding whether it is a picture of a cat. Cat pictures vary. What does a system need to know in order to decide? What if the cat is wet and the fur is matted? The photograph could be of a tiger or a kitten or a toy cat. The pictures could differ in many ways such as in the lighting or viewpoint and whether things obscure the picture. Should a ceramic “Hello Kitty” toy be classified as a cat? The large number of possible variations makes such image classification very difficult. It would take a long time to write down the detailed rules of such a process.

The breakthrough advantage in this example is that deep learning systems for image recognition do not require people to write down exactly what to do. The systems just need a large amount of data. Some photographs are labeled as “cats” and others are labeled differently. Given a very large number of examples, the learning system creates a mathematical boundary curve between “cat” and “not a cat”. This curve has many twists and bumps and bends to accommodate the observed variations in the training data. Eventually, the refined curve gets very good at recognizing cats or doing some other classification task.

Here’s where the explanation challenge comes up. Remember all those little wrinkles and bends. They describe a boundary curve in a very high-dimensional mathematical space. The curve maps out differences in photographs, but the system cannot explain what it knows or what it does.

We may not worry much about whether a cat recognition system always gets a good answer. On the other hand, consider applications like self-driving cars. Although these systems are not entirely based on machine learning, the problem is the same. When a self-driving car has an accident, we want to know why it failed. Is it safe to rely on automatic driving at night? How about driving around schools, where there are unpredictable kids on bicycles and skateboards? How about when a car is facing the sun and a white trailer truck is crossing the highway? What are the conditions under which the system has been adequately trained? Can it explain when it is safe to use? What it doesn’t know and what we don’t understand about it can kill people.

So the XAI challenge is about not only training for performance, but also creating systems that can explain and be aware of their own limitations.

What are some ways that you’ve seen these challenges addressed?

There are two groups of people who are trying to address how to make AI systems be explainable. First, there are the mathematicians and computer scientists who approach the XAI challenge from the perspective of algorithms and representations. Then, there are sociologists, linguists, and psychologists who ask, What is an explanation?”, and “What kinds of explanations do people need?”

From a math and computer science point of view, most of the research has focused on representations of explanations that are “interpretable”. For example, an interpretability approach may reformulate the numbers embedded in a neural network in terms of a collection of rules. The rules give a sense of decisions made by the system: “If x is true and y is true, then conclude z.” When people see rules in a decision tree they many say, “Oh I see. Here is a rule for how the system decides something.”

Researchers working from a psychological or human-centered perspective do not stop with interpretability. If the decision is really complicated—such as in the cat recognition example—the set of rules required to describe that process could easily be hundreds of pages long. Interpretability approaches fail to address complexity.

From a human-centered perspective, explanation needs to address not only the representation of information, but also the sensemaking requirements for the users. What information do people need to know? Psychologists have studied people explaining things to each other. When people with very different backgrounds work together, they share terminology. Their dialog goes back and forth as they learn to understand each other. For computers to work with humans in complex situations, a similar process for explanation and common grounding will be needed.

How hard is that to actually do?

We have studied people trying to understand AI systems. They often think about an AI in a similar way to how they think about the other intelligent agents they know about, that is, other people. Viewing an AI’s actions, they ask themselves, “What would I do in this situation?” If the AI deviates from that, they say, “Oh, now it’s being irrational.”

This phenomenon reveals an important point about explanations. People project their own rationality on the AI, which often differs from how the AI actually thinks. To overcome this tendency, explanations need to teach. The purpose of an explanation is to teach people what it thinks. An explanation may be about a local consideration such as, “Why does the AI choose this alternative over that one?” For a different kind of example, an AI may fail on something because it lacks some competency. It makes mistakes because there is something that it does not know. In this case explanations should describe where training is thin or where the results are less stable.

People who have watched toddlers have seen exploratory behavior related to this. Kids do tiny experiments in the world: playing with blocks, watching others, watching how the world works, and learning language. Toddlers build up commonsense knowledge a little at a time. In some approaches, AI systems start from a very simple beginning. Before these AIs can achieve task-level competencies, they first need to learn things that toddlers know. They need to learn to perceive their environment, how things move, and so on.

People also learn to use approximations. Approximations enable us to make estimates even when we lack some data. They let us think more deeply by taking big steps instead of little ones. Meeting human memory limitations, approximations and abstractions make it easier to solve problems and also to explain our solutions. Using approximating abstractions is part of both common sense and common ground.

This process of learning common sense is an interesting part of AI and machine learning and relates to research on human childhood development. It also connects to fundamental challenges for XAI. AI researchers and other people are sometimes surprised that machines don’t know things that we take for granted because we learned them as toddlers. For this reason, I like to say that common sense and common ground are the biggest challenges for XAI.

Where do you see the greatest potential for AI applications and developments in the next ten years?

In ten years, I see an opportunity—a really big potential—for creating machines that learn in partnerships with people. At PARC we are interested in an idea that we call mechagogy, which means human-machine partnerships where humans and machines teach each other. Mechagogy research combines the strengths of people and computers.

There’s an asymmetry between what people can do well and what machines can do well, and human-machine partnerships are a possible way to explore that. In the future, AI systems will become part of the workplace more easily when they can be genuine partners.

Reflecting on the research challenges of common ground and common sense for XAI, a path to creating human-machine partnerships may involve a new kind of job: AI curators. Imagine that the people who use AIs as partners take responsibility for training the AIs. Who better could know the next set of on-the-job challenges? This is a largely unexplored but open space for opportunities for AI. And it depends on XAI, because who wants a partner that can’t explain itself?

Learn more about Explainable AI at PARC.

Thursday, 26 September 2019

Brand Safety with Structured Streaming, Delta Lake, and Databricks

The original blog is from Eyeview Engineering’s blog Brand Safety with Spark Streaming and Delta Lake reproduced with permission.

Eyeview serves data-driven online video ads for its clients. Brands know the importance of ad placement and ensuring their ads are not placed next to unfavorable content. The Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB), defines brand safety as keeping a brand’s reputation safe when they advertise online. In practice, this means avoiding the ads placement next to inappropriate content. The content of the webpage defines the segments of that page URL (e.g. CNN.com has news about the presidential election, then politics can be segments of that page).

Brand Safety at Eyeview

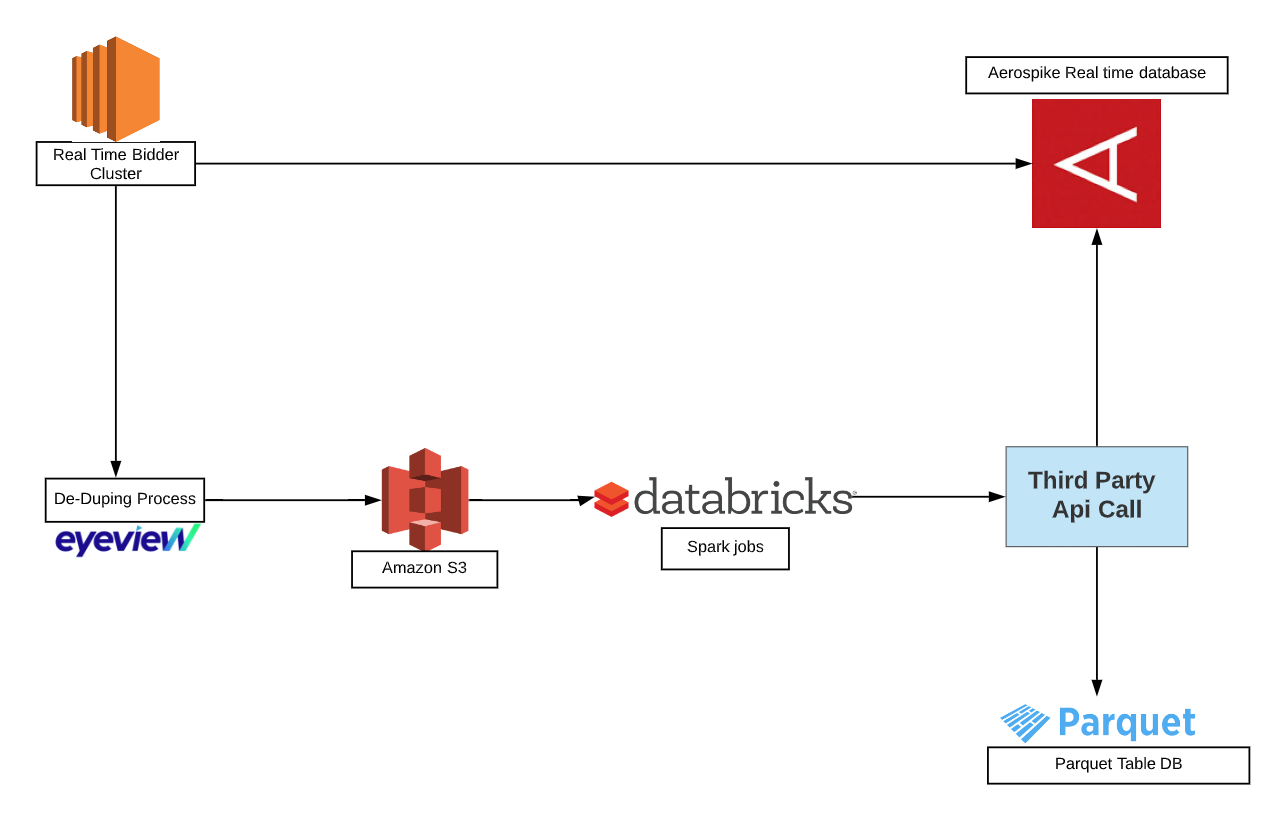

The diagram below shows how Eyeview implemented the concept of brand safety and what challenges were faced.

Eyeview’s cluster of real-time bidders requires the information on whether a URL is brand safe or not in order to make the decision to serve the ad. It gets this information from Aerospike (our real-time database with latency close to 10ms), but to persist this information in Aerospike we defined an offline solution that loads the segment information. Once Eyeview’s cluster of bidders gets the bid request, the URL of that bid request is dumped into S3. The number of requests the cluster gets is close to 500k requests per second. Getting numerous URLs every second dumped into S3 after the deduping process (so that HTTP call is not made for the same URLs multiple times in the same timeframe) can create a massive problem processing a large number of small files simultaneously.

Big Data Challenges

Many of the developers in the big data world face this problem in Spark or Hadoop environments. Below is the list of challenges that can arise while batch processing a large number of small files.

Challenge #1: Underutilized Resources

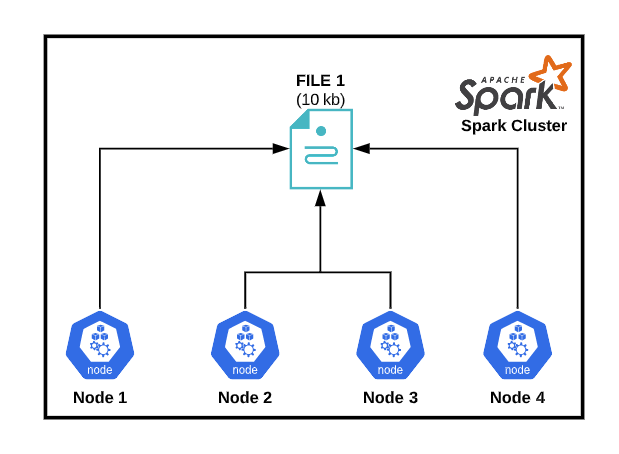

Underutilizing the cluster resources (seen in the photo below) for reading a small size file (~KB size) using a 1TB cluster would be like cutting bread using a sword instead of a butter knife.

Challenge #2: Manual Checkpointing

It is important to perform manual checkpointing to track which files were processed and which were not. This can be extremely tedious in cases involving reprocessing of files or failures. Also, this may not be scalable if the data size becomes very large.

Challenge #3: Parquet Table Issues

Let’s assume somehow we managed to process these large number of small files and we are not caching/persisting data on the cluster and writing directly to a parquet table via Spark, we then would end up writing too many small files to the tables. The problem with parquet files is that the continuous append on the table is too slow. We leveraged overwrite mode to save the data which ended up creating millisecond partitions to table.

Challenge #4: No Concurrent Reads on Parquet Tables

The latency of the offline jobs became so high that the job was continuously writing the data to the parquet tables, which means no other jobs can query that table and parquet does not work great with a very large number of partitions.

Databricks Spark Streaming and Delta Lake

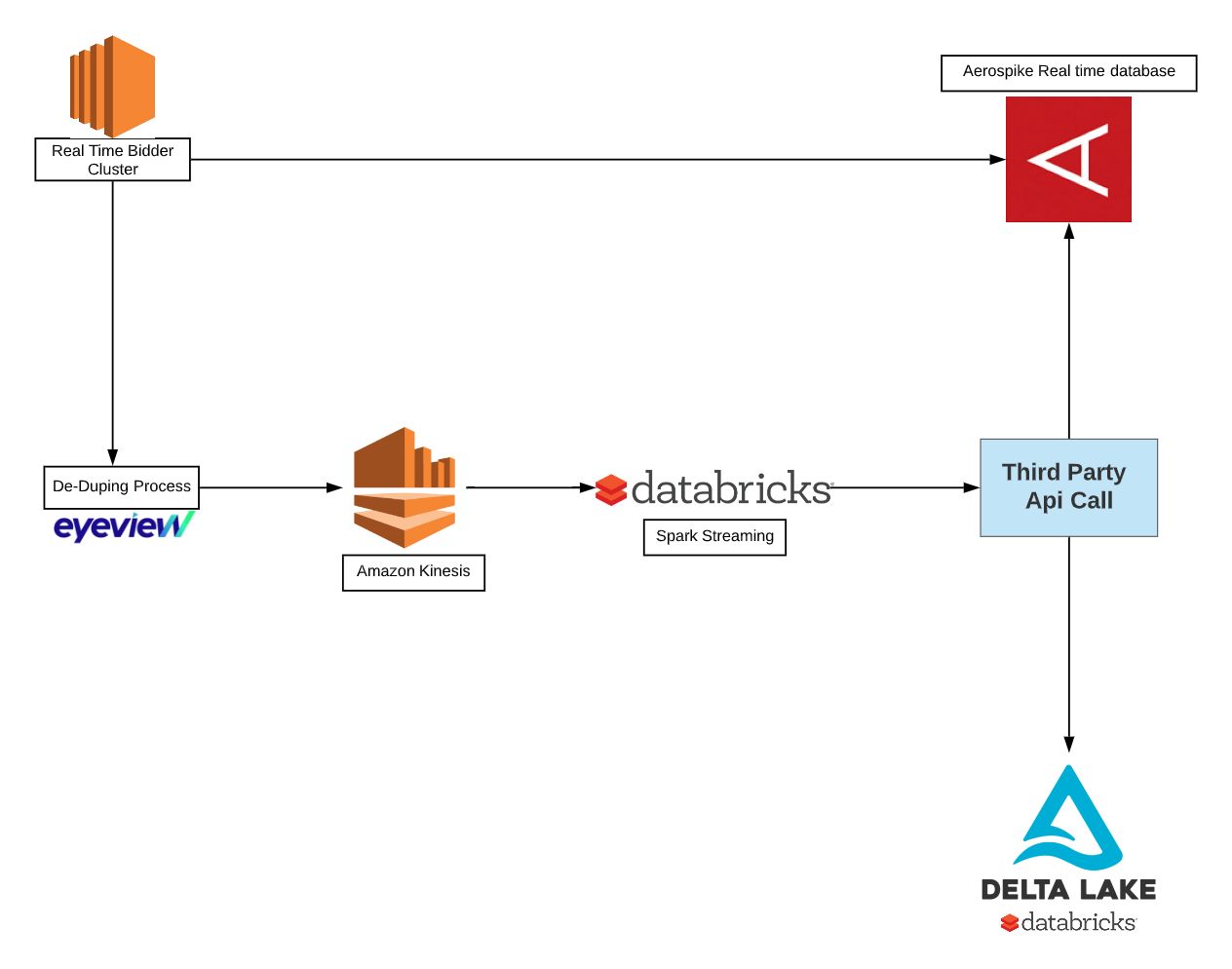

To solve the above challenges we introduced two new technologies: Databricks Spark Streaming and Delta Lake. The source of most of a large number of small files can be converted from batch processing to streaming processing. Databricks Spark streaming helped in solving the first two challenges. Instead of a cluster of bidders writing files which contain the URLs to S3, we started sending URLs directly to a kinesis stream. This way we didn’t have a small number of files; all the data is in the streams, which would lead to utilizing our Spark resources efficiently.

By connecting Spark Streaming with Kinesis streams we no longer need to do manual checkpointing. Since Spark Streaming is inherently fault-tolerant we don’t have worry about failures and reprocessing of files. The code snippet below reads the data from the Kinesis stream.

import org.apache.spark.sql.types._

val jsonSchema = new StructType()

.add("entry", StringType)

.add("ts", LongType)

val kinesisDF = spark.readStream

.format("kinesis")

.option("streamName", "kinesis Stream Name")

.option("initialPosition", "LATEST")

.option("region", "aws-region")

.load()

val queryDf = kinesisDF

.map(row => Charset.forName("UTF-8").newDecoder().decode(ByteBuffer.wrap(new Base64().decode(row.get(1)).asInstanceOf[Array[Byte]])).toString)

.selectExpr("cast (value as STRING) jsonData")

.select(from_json(col("jsonData"), jsonSchema).as("bc"))

.withColumn("entry",lit($"bc.entry"))

.withColumn("_tmp", split($"entry", "\\,"))

.select(

$"_tmp".getItem(0).as("device_type"),

$"_tmp".getItem(1).as("url"),

$"_tmp".getItem(2).as("os"),

$"bc.ts".as("ts")

).drop("_tmp")

The other two challenges with the parquet table are solved by introducing a new table format, Delta Lake. Delta Lake supports ACID transactions, which basically means we can concurrently and reliably read/write this table. Delta Lake tables are also very efficient with continuous appends to the tables. A table in Delta Lake is both a batch table, as well as a streaming source and sink. The below code shows persisting the data into delta lake. This also helped us in removing the millisecond partitions; see the below code for reference (partitions are up to only hour level).

val sparkStreaming = queryDf.as[(String,String,String,Long)].mapPartitions{partition=>

val http_client = new HttpClient

http_client.start

val partitionsResult = partition.map{record=>

try{

val api_url = ApiCallingUtility.createAPIUrl(record._2,record._1,record._3)

val result = ApiCallingUtility.apiCall(http_client.newRequest(api_url).timeout(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS).send(),record._2,record._1)

aerospikeWrite(api_url,result)

result

}

catch{

case e:Throwable=>{

println(e)

}

}

}

partitionsResult

}

Conclusion and Results

By default, our cluster of bidders makes no bid as the decision if the bidders did not have segment information of a URL. This would result in less advertising traffic which would have a substantial monetary impact. The latency of the old architecture was so high that the result was filtered out URLs – i.e. no ads. By switching the process to Databricks Spark Streaming and Delta Lake, we decreased the number of bid calls to be filtered by 50%! Once we had moved the architecture from batch processing to a streaming solution, we were able to reduce the cluster size of the Spark jobs, thus significantly reducing the cost of the solution. More impressively, now we only require one job to take care of all the brand safety providers, which further reduced costs.

--

Try Databricks for free. Get started today.

The post Brand Safety with Structured Streaming, Delta Lake, and Databricks appeared first on Databricks.

Chart.js Example with Dynamic Dataset