Data Science, Machine Learning, Natural Language Processing, Text Analysis, Recommendation Engine, R, Python

Saturday, 30 March 2019

Daimler buys Torc Robotics stake for self-driving trucks

The journey of becoming a Jenkins contributor: Introduction

As a software engineer, for many years I have used open source software (frameworks, libraries, tools…) in the different companies I have worked at. However, I had never been able to engage in an open-source project as a contributor, until now.

Since I made my first—ridiculously simple—commit into Jenkins, six months ago (in September, 2018), I have been attempting to contribute more to the Jenkins project. However, contributing to open-source projects is, in general, challenging. Especially to long-lived projects, with a lot of history, legacy code and tribal knowledge. It is often difficult to know where to start and also difficult to come up with a plan to keep moving forward and contributing regularly, and in more meaningful ways over time.

When it comes to the Jenkins project, I have encountered challenges that others trying to get into the community are likely to encounter. For that reason, I have decided to go ahead and share my journey of becoming a more engaged Jenkins contributor.

I plan to publish roughly 1 post per month, describing this journey. I will attempt to start contributing to the pieces that are easier to start with, transitioning towards more complex contributions over time.

Where to start

jenkins.io

To become a Jenkins contributor, the most obvious place to start looking at is jenkins.io. In the top navbar there is a Community dropdown, with several links to different sections. The first entry, Overview, takes us to the “Participate and contribute” section.

In this section we get lots of information about the many ways in which we can engage with the Jenkins project and community. Even though the intention is to display all the possible options, allowing the reader to choose, it can feel a bit overwhelming.

The page is divided into two columns, the column on the left shows the different options to participate, while the column on the right shows the different options to contribute.

Suggestions to Participate

In the left column of the “Participate and contribute” page, there are several ideas on how to engage with the community, ranging from communicating to reviewing changes or providing feedback.

One of the pieces that got me confused at first in this area were the communication channels. There are many different channels for communication. There are several mailing lists and there are also IRC and Gitter channels.

During my first attempts to get involved, I subscribed to many of the mailing lists and several IRC and Gitter channels, but I quickly noticed that there is significant communication going on; and that most threads in the most active lists and channels are specific to issues users or developers have. So, unless your goal is to support other users right away (if you are an experienced Jenkins user already it might be the case) or you plan to ask questions that you already have in mind, I would advise against spending too much time on this at first.

Even though it is great to see how the community members support each other, the amount of communication might be overwhelming for a newcomer, and if you are also trying to contribute to the project (either with translations, documentation or code), following these conversations might not be the best way to start.

Suggestions to Contribute

In the right column of the “Participate and contribute” page there are several ideas on how to contribute, mostly grouped into: writing code, translating, documenting and testing.

In following posts, I will be going through all of these types of contributions, as well as through some of the suggestions to participate, which include reviewing Pull Requests (PRs) or providing feedback (either reporting new issues or replicating cases other users have already described, providing additional information to help the maintainer reproduce and fix them).

My first contribution in this journey

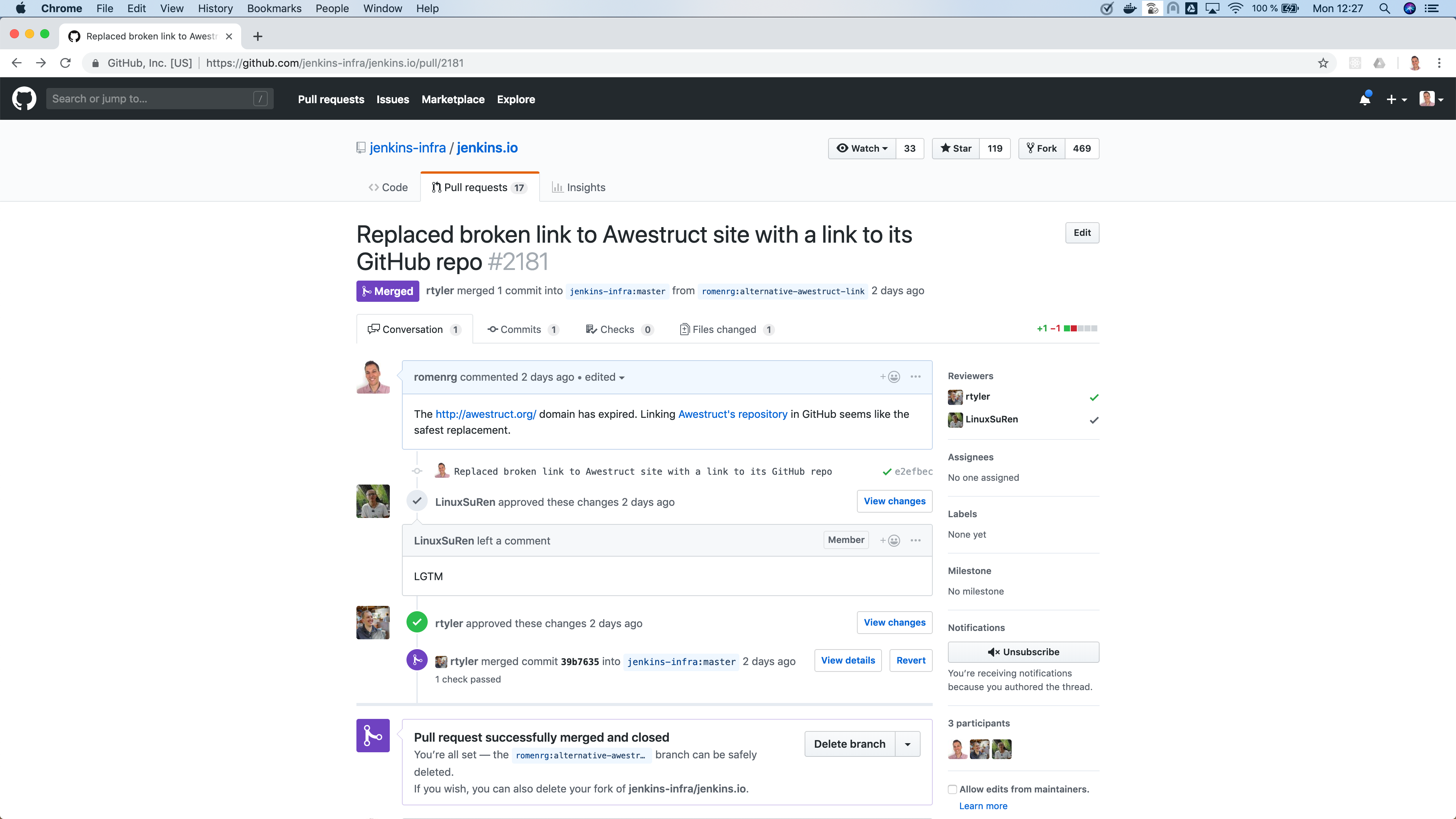

When looking at the “Participate and contribute” page, I noticed a couple of things in that page that I could help improve. And I was actually planning to pick one of those as the first example of a contribution for this post. But when I was reading the contributing guidelines of the repository, I found an even easier contribution I could make, which I thought would be a great example to illustrate how simple it could be to start contributing. So I decided to go ahead with it.

The website repository

In the ”Document” section there is a link to the contributing guidelines of the jenkins.io repository. The CONTRIBUTING file is a common file present in the root folder of most open-source-project repositories.

Following the link to that file, I reached the jenkins.io repository, which is the one that contains the sources for the corresponding website—which also includes this blog. And, in fact, the contributing file was the first file I wanted to review, in order to learn more about how to contribute to the website.

Found a broken link

When reading the contributing file, I learned about the Awestruct static site generator, which is the tool used to transform the AsciiDoc source files in the repo into a website. However, when I clicked the link to learn more about it, I noticed it was broken. The domain had expired.

Why not fix it?

This was the opportunity I chose to show other newcomers how easy it can be to start contributing.

Forking the repository

The first step, as usual, would be to fork the repository and clone it to my machine.

Applying the change

The next step would be to apply the change to the corresponding file. To do so, I created a new branch “alternative-awestruct-link” and applied the change there:

Making sure everything builds correctly and tests pass

Even though in this case my contribution was not to the actual website, but to the contributing guidelines (and for that reason was unlikely to break anything), it is a best practice to get used to the regular process every contribution should follow, making sure everything builds correctly after any change.

As stated in the contributing guidelines themselves, in order to build this repository we just have to run the default “make” target, in the root of the repository.

Once the command execution finishes, if everything looks good, we are ready to go to the next step: creating the PR.

Creating the PR

Once my change had been committed and pushed to my repository, I just had to create the PR. We have an easy way to do so by just clicking the link that we get in our git logs once the push is completed, although we can create the PR directly through the GitHub UI, if we prefer so; or even use “hub”, the GitHub CLI, to do it.

In this case, I just clicked the link, which took me to the PR creation page on GitHub. Once there, I added a description and created the PR.

When a PR to this repository is created, we notice there are some checks that start running. Jenkins repositories are configured to notify the “Jenkins on Jenkins”, which runs the corresponding CI pipelines for each repository, as described in the corresponding Jenkinsfile.

Once the checks are completed, we can see the result in the PR:

And if we want to see the details of the execution, we can follow the “Show all checks” link:

I have contributed!

This contribution I made is a trivial one, with very little complexity and it might not be the most interesting one if you are trying to contribute code to the Jenkins project itself.

However, for me, as the contributor, it was a great way to get familiar with the repository, its contributing guidelines, the technology behind the jenkins.io website; and, above anything else, to start “losing the fear” of contributing to an open source project like Jenkins.

So, if you are in the same position I was, do not hesitate. Go ahead and find your own first contribution. Every little counts!

Friday, 29 March 2019

Improving Data Management and Analytics in the Federal Government

From Static Data Warehouse to Scalable Insights and AI On-Demand

Government agencies today are dealing with a wider variety of data at a much larger scale. From satellite imagery to sensor data to citizen records, petabytes of semi- and unstructured data is collected each day. Unfortunately, traditional data warehouses are failing to provide government agencies with the capabilities they need to drive value out of their data in today’s big data world. In fact, 73% of federal IT managers report that their agency not only struggles with harnessing and securing data, but also faces challenges analyzing and interpreting it1. Some of the most common pain points facing data teams in the federal government include:

- inelastic and costly compute and storage resources

- rigid architectures that require teams to build time-consuming ETL pipelines

- limited support for advanced analytics and machine learning

Fortunately, Databricks Unified Analytics Platform powered by Apache SparkTM provides a fast, simple, and scalable way to augment your existing data warehousing strategy by combining pluggable support for a broad set of data types and sources, scalable compute on-demand and the ability to perform low latency queries in real-time rather than investing in complicated and costly ETL pipelines. Additionally, Databricks provides the tools necessary for advanced analytics and machine learning, future proofing your analytics.

Join our three-part webinar series to learn:

- Part 1: How to build a modern data analytics solution for the Fed Government with Apache Spark and the Databricks Unified Analytics Platform

- Part 2: How to simplify ETL and change data capture (CDC) processes to support your data engineering and data science initiatives.

- Part 3: How to enrich your modern analytics platform with machine learning and deep learning

Learn More

- Register for part one of our webinar series

- Learn how the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Sevatec and other agencies are adopting Databricks to drive digital transformation

--

Try Databricks for free. Get started today.

The post Improving Data Management and Analytics in the Federal Government appeared first on Databricks.

The Organisation of Tomorrow – Available Soon!

Big data analytics empower consumers and employees, resulting in open strategy and a better understanding of the changing environment. Blockchain enables peer-to-peer collaboration and trustless interactions. And, AI facilitates new and different levels of involvement among human and artificial actors.

From these interactions and responses, new modes of organising are emerging, where technology facilitates collaboration between stakeholders and where human-to-human interactions are increasingly replaced with human-to-machine and even machine-to-machine interactions.

My New Book: The Organisation of Tomorrow

As a result, emerging technologies change organisations as we know them. Organisations that want to remain competitive in this changing environment need to anticipate shifting behaviours of stakeholders and technologies. To help organisations address the challenges of the exponential times we live in, I turned my PhD dissertation into an easy-to-read and digest management book.

This book offers organisations a blueprint for ...

Read More on Datafloq

3 Factors that Will Alter Demand for Data Analysts Over the Next Decade

These types of economic forecasts tend to be reasonably accurate. However, it is difficult to cite them with exact precision. A number of conflating factors could reduce or increase the demand for data analytics jobs in the foreseeable future.

Here are some of the factors that could impact future demand for this rapidly growing profession.

A shortage of skilled data professionals could temper demand

Supply and demand for big data professionals is a two-way street. If there is a shortage of people willing and able to fulfill the job requirements, then demand could also stagnate.

Why would this occur? If new startups can’t attract reliable data professionals, then they may have to fold. This could lessen the number of big data startups, which in turn would cause the demand for entry-level big data analytics service jobs to decline.

The outlook is not ...

Read More on Datafloq

How Data Tech is Supporting the Growing Gig Economy

This type of professional lifestyle is also incredibly attractive to younger generations entering the workforce, but it is certainly not limited to Millennials and recent college grads. More and more workers are finding ways to turn a side hustle into a major money maker. In fact, over one-third of the American workforce currently uses an “alternative work arrangement” as their primary source of income.

The great news is that as the gig economy grows, businesses are finding ways to incorporate data technology to ensure that opportunities abound and alternative entrepreneurs can succeed.

Let’s discuss how some of the latest trends in technology are making it possible for the gig economy to continue on its upward trajectory.

Cloud-Based Accounting Tools for Better Freelance Billing

One of the things that attracts most freelancers to the gig economy is the fact that they can set their own ...

Read More on Datafloq

Multi-Sensor Data Fusion (MSDF) and AI: The Case of AI Self-Driving Cars

By Lance Eliot, the AI Trends Insider

A crucial element of many AI systems is the capability to undertake Multi-Sensor Data Fusion (MSDF), consisting of collecting together and trying to reconcile, harmonize, integrate, and synthesize the data about the surroundings and environment in which the AI system is operating. Simple stated, the sensors of the AI system are the eyes, ears, and sensory input, while the AI must somehow interpret and assemble the sensory data into a cohesive and usable interpretation of the real world.

If the sensor fusion does a poor job of discerning what’s out there, the AI is essentially blind or misled toward making life-or-death algorithmic decisions. Furthermore, the sensor fusion needs to be performed on a timely basis. Any extra time taken to undertake the sensor fusion means there is less time for the AI action planning subsystem to comprehend the driving situation and figure out what driving actions are next needed.

Humans do sensor fusion all the time, in our heads, though we often do not overtly put explicit thought towards our doing so. It just happens, naturally. We do the sensor fusing by a kind of autonomic process, ingrained by our innate and learned abilities of fusing our sensory inputs from the time we are born. On some occasions, we might be sparked to think about our sensor fusing capacities, if the circumstance catches our attention.

The other day, I was driving in the downtown Los Angeles area. There is always an abundance of traffic, including cars, bikes, motorcycles, scooters, and pedestrians that are prone to jaywalking. There is a lot to pay attention to. Is that bicyclist going to stay in the bike lane or decide to veer into the street? Will the pedestrian eyeing my car decide to leap into the road and dart across the street, making them a target and causing me to hit the brakes? It is a free-for-all.

I had my radio on, listening to the news reports, when I began to faintly hear the sound of a siren, seemingly off in the distance. Maybe it was outside, or maybe it was inside the car — the siren might actually be part of a radio segment covering the news of a local car accident that had happened that morning on the freeway, or was it instead a siren somewhere outside of my car? I turned down my radio. I quickly rolled down my driver’s side window.

As I strained to try and hear a siren, I also kept my eyes peeled, anticipating that if the siren was occurring nearby, there might be a police car or ambulance or fire truck that might soon go skyrocketing past me. These days it seems like most driver’s don’t care about emergency vehicles and fail to pull over to give them room to zoom along. I’m one of those motorists that still thinks we ought to help out by getting out of the way of the responders (plus, it’s the law in California, as it is in most states).

Of course, it makes driving sense anyway to get out of the way, since otherwise you are begging to get into a collision with a fast-moving vehicle, which doesn’t seem like a good idea on anyone’s behalf. A few years ago, I saw the aftermath of a collision between a passenger car and an ambulance. The two struck each other with tremendous force. The ambulance ended-up on its side. I happened to drive down the street where the accident had occurred, and the recovery crews were mopping up the scene. It looked outright frightening.

In any case, I was listening intently in the case of my driving in downtown Los Angeles and trying to discern if an emergency vehicle was in my vicinity and warning to be on the watch for it. I could just barely hear the siren. My guess was that it had to be a few blocks away from me. Was it thought getting louder and getting nearer to me, or was it fading and getting further away?

I decided that the siren was definitely getting more distinctive and pronounced. The echoes along the streets and buildings was creating some difficulty in deciding where the siren was coming from. I could not determine if the siren was behind me or somewhere in front of me. I couldn’t even tell if the siren was to my left or to my right. All I could seem to guess is that it was getting closer, one way or another.

At times like this, your need to do some sensor fusion is crucial. Your eyes are looking for any telltale sign of an emergency vehicle. Maybe the flashing lights might be seen from a distance. Perhaps other traffic might start to make way for the emergency vehicle, and that’s a visual clue that the vehicle is coming from a particular direction. Your ears are being used to do a bat-like echolocation of the emergency vehicle, using the sound to gauge the direction, speed, and placement of the speeding object.

I became quite aware of my having to merge together the sounds of the siren with my visual search of the traffic and streets. Each was feeding the other. I could see traffic up ahead that was coming to a stop, doing so even though they had a green light. It caused me to roll down my other window, the front passenger side window, in hopes of aiding my detection of the siren. Sure enough, the sound of the siren came through quite a bit on the right side of my car, more so than the left side of the car. I turned my head toward the right, and in moments saw the ambulance that zipped out of a cross-street and came into the lanes ahead.

This is the crux of Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. I had one kind of sensor, my eyes, providing visual inputs to my brain. I had another kind of sensor, my ears, providing acoustical inputs to my brain. My brain managed to tie together the two kinds of inputs. Not only were the inputs brought together, they were used in a means of each aiding the other. My visual processing led me to listen toward the sound. The sound led me to look toward where the sound seemed to be coming from.

My mind, doing some action planning of how to drive the car, melded together the visual and the acoustic, using it to guide how I would drive the car. In this case, I pulled the car over and came to a near stop. I also continued to listen to the siren. Only once it had gone far enough away, along with my not being able to see the emergency vehicle anymore, did I decide to resume driving down the street.

This whole activity of my doing the sensor fusion was something that played out in just a handful of seconds. I know that my describing it seemed to suggest that it took a long time to occur, but the reality is that the whole thing happened like this, hear siren, try to find siren, match siren with what I see, pull over, wait, and then resume driving once safe to do so. It is a pretty quick effort. You likely do the same from time-to-time.

Suppose though that I was wearing my ear buds and listening to loud music while driving (not a wise thing to do when driving a car, and usually illegal to do while driving), and did not hear the siren? I would have been solely dependent upon my sense of sight. Usually, it is better to have multiple sensors active and available when driving a car, giving you a more enriched texture of the traffic and the driving situation.

Notice too that the siren was hard to pin down in terms of where it was coming from, along with how far away it was. This highlights the aspect that the sensory data being collected might be only partially received or might otherwise be scant, or even faulty. Same could be said about my visually trying to spot the emergency vehicle. The tall buildings blocked my overall view. The other traffic tended to also block my view. If it had been raining, my vision would have been further disrupted.

Another aspect involves attempting to square together the inputs from multiple sensors. Imagine if the siren was getting louder and louder, and yet I did not see any impact to the traffic situation, meaning that no other cars changed their behavior and those pedestrians kept jaywalking. That would have been confusing. The sounds and my ears would seem to be suggesting one thing, while my eyes and visual processing was suggesting something else. It can be hard at times to mentally resolve such matters.

In this case, I was alone in my car. Only me and my own “sensors” were involved in this multi-sensor data fusion. You could have more such sensors, such as when having passengers that can aid you in the driving task.

Peering Into The Fog With Multiple Sensory Devices

I recall during my college days a rather harried driving occasion. While driving to a college basketball game, I managed to get into a thick bank of fog. Some of my buddies were in the car with me. At first, I was tempted to pull the car over and wait out the fog, hoping it would dissipate. My friends in the car were eager to get to the game and urged me to keep driving. I pointed out that I could barely see in front of the car and had zero visibility of anything behind the car.

Not the best way to be driving at highway speeds on an open highway. Plus, it was night time. A potent combination for a car wreck. It wasn’t just me that I was worried about, I also was concerned for my friends. And, even though I thought I could drive through the fog, those other idiot drivers that do so without paying close attention to the road were the really worrisome element. All it would take is some dolt to ram into me or opt to suddenly jam on their brakes, and it could be a bad evening for us all.

Here’s what happened. My buddy in the front passenger seat offered to intently watch for anything to my right. The two friends in the back seat were able to turnaround and look out the back window. I suddenly had the power of six additional eyeballs, all looking for any other traffic. They began each verbally reporting their respective status. I don’t see anything, one said. Another one barked out that a car was coming from my right and heading toward us. I turned my head and swerved the car to avoid what might have been a collision.

Meanwhile, both of the friends in the backseat yelled out that a car was rapidly approaching toward the rear of the car. They surmised that the driver had not seen our car in the fog and was going to run right up into us. I hit the gas to accelerate forward, doing so to gain a distance gap between me and the car from behind. I could see that there wasn’t a car directly ahead of me and so leaping forward was a reasonable gambit to avoid getting hit from behind.

All in all, we made it to the basketball game without nary a nick. It was a bit alarming though and a situation that I will always remember. There we were, working as a team, with me as the driver at the wheel. I had to do some real sensor fusion. I was receiving data from my own eyes, along with hearing from my buddies, and having to mentally combine together what they were telling me with what I could actually see.

When you are driving a car, you often are doing Multi-Target Tracking (MTT). This involves identifying particular objects or “targets” that you are trying to keep an eye on. While driving in downtown Los Angeles, my “targets” included the many cars, bike rides, and pedestrians. While driving in the foggy evening, we had cars coming from the right and from behind.

Your Field of View (FOV) is another vital aspect of driving a car and using your sensory apparatus. During the fog, my own FOV was narrowed to what I could see on the driver’s side of the car, and I could not see anything from behind the car. Fortunately, my buddies provided additional FOV’s. My front passenger was able to augment my FOV by telling me what was seen to the right of the car. The two in the backseat had a FOV of what was behind the car.

Those two stories that I’ve told are indicative of how we humans do our sensor fusion while driving a car. As I earlier mentioned, we often don’t seemingly put any conscious thought to the matter. By watching a teenage novice driver, you can at times observe as they struggle to do sensor fusion. They are new to driving and trying to cope with the myriad of details to be handled. It is a lot to process, such as keeping your hands on the wheel, your feet on the pedals, your eyes on the road, along with having to mentally process everything that is happening, all at once, in real-time.

It can be overwhelming. Seasoned drivers are used to it. But seasoned drivers can also find themselves in situations whereby sensor fusion becomes an outright imperative and involves very deliberate attention and thought. My fog story is somewhat akin to that kind of situation, similarly my siren listening story is another example.

In the news recently there has been the story about the Boeing 737 MAX 8 airplane and in particular two horrific deadly crashes. Some believe that the sensors on the plane were a significant contributing factor to the crashes. Though the matters are still being investigated, it is a potential example of the importance of Multi-Sensor Data Fusion and has lessons that can be applied to driving a car and advanced automation used to do so.

For the Boeing situation as it applies to self-driving cars, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/boeing-737-max-8-and-lessons-for-ai-the-case-of-ai-self-driving-cars/

For more about the fundamentals of sensor fusion, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/sensor-fusion-self-driving-cars/

For why one kind of sensor having just is myopic, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/cyclops-approach-ai-self-driving-cars-myopic/

For my article about what happens when sensors go bad or faulty, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/going-blind-sensors-fail-self-driving-cars/

Multi-Sensor Data Fusion for AI Self-Driving Cars

What does this have to do with AI self-driving cars?

At the Cybernetic AI Self-Driving Car Institute, we are developing AI software for self-driving cars. One important aspect involves the design, development, testing, and fielding of the Multi-Sensor Data Fusion.

Allow me to elaborate.

I’d like to first clarify and introduce the notion that there are varying levels of AI self-driving cars. The topmost level is considered Level 5. A Level 5 self-driving car is one that is being driven by the AI and there is no human driver involved. For the design of Level 5 self-driving cars, the auto makers are even removing the gas pedal, brake pedal, and steering wheel, since those are contraptions used by human drivers. The Level 5 self-driving car is not being driven by a human and nor is there an expectation that a human driver will be present in the self-driving car. It’s all on the shoulders of the AI to drive the car.

For self-driving cars less than a Level 5, there must be a human driver present in the car. The human driver is currently considered the responsible party for the acts of the car. The AI and the human driver are co-sharing the driving task. In spite of this co-sharing, the human is supposed to remain fully immersed into the driving task and be ready at all times to perform the driving task. I’ve repeatedly warned about the dangers of this co-sharing arrangement and predicted it will produce many untoward results.

For my overall framework about AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/framework-ai-self-driving-driverless-cars-big-picture/

For the levels of self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/richter-scale-levels-self-driving-cars/

For why AI Level 5 self-driving cars are like a moonshot, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/self-driving-car-mother-ai-projects-moonshot/

For the dangers of co-sharing the driving task, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/human-back-up-drivers-for-ai-self-driving-cars/

Let’s focus herein on the true Level 5 self-driving car. Much of the comments apply to the less than Level 5 self-driving cars too, but the fully autonomous AI self-driving car will receive the most attention in this discussion.

Here’s the usual steps involved in the AI driving task:

- Sensor data collection and interpretation

- Sensor fusion

- Virtual world model updating

- AI action planning

- Car controls command issuance

Another key aspect of AI self-driving cars is that they will be driving on our roadways in the midst of human driven cars too. There are some pundits of AI self-driving cars that continually refer to a utopian world in which there are only AI self-driving cars on the public roads. Currently there are about 250+ million conventional cars in the United States alone, and those cars are not going to magically disappear or become true Level 5 AI self-driving cars overnight.

Indeed, the use of human driven cars will last for many years, likely many decades, and the advent of AI self-driving cars will occur while there are still human driven cars on the roads. This is a crucial point since this means that the AI of self-driving cars needs to be able to contend with not just other AI self-driving cars, but also contend with human driven cars. It is easy to envision a simplistic and rather unrealistic world in which all AI self-driving cars are politely interacting with each other and being civil about roadway interactions. That’s not what is going to be happening for the foreseeable future. AI self-driving cars and human driven cars will need to be able to cope with each other.

For my article about the grand convergence that has led us to this moment in time, see: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/grand-convergence-explains-rise-self-driving-cars/

See my article about the ethical dilemmas facing AI self-driving cars: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/ethically-ambiguous-self-driving-cars/

For potential regulations about AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/assessing-federal-regulations-self-driving-cars-house-bill-passed/

For my predictions about AI self-driving cars for the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s, see my article: https://aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/gen-z-and-the-fate-of-ai-self-driving-cars/

Returning to the topic of Multi-Sensor Data Fusion, let’s walk through some of the key essentials of how AI self-driving cars undertake such efforts.

Take a look at Figure 1.

I’ve shown my overall framework about AI self-driving cars and highlighted the sensor fusion stage of processing.

Per my earlier remarks about the crucial nature of sensor fusion, consider that if the sensor fusion goes awry, it means that the stages downstream are going to be either without needed information or be using misleading information. The virtual world model won’t be reflective of the real-world surrounding the self-driving car. The AI action planning stage will not be able to make appropriate determinations about what the AI self-driving car actions should be.

One of the major challenges for sensor fusion involves dealing with how to collectively stich together the multitude of sensory data being collected.

You are going to have the visual data collected via the cameras, coming from likely numerous cameras mounted at the front, back, and sides of the self-driving car. There is the radar data collected by the multiple radar sensors mounted on the self-driving car. There are likely ultrasonic sensors. There could be LIDAR sensors, a special kind of sensor that combines light and radar. And there could be other sensors too, such as acoustic sensors, olfactory sensors, etc.

Thus, you will have to stich together sensor data from like-sensors, such as the data from the various cameras. Plus, you will have to stitch together the sensor data from unlike sensors, meaning that you want to do a kind of comparison and contrasting with the cameras, with the radar, with the LIDAR, with the ultrasonic, and so on.

Each different type or kind of sensor provides a different type or kind of potential indication about the real-world. They do not all perceive the world in the same way. This is both good and bad.

The good aspect is that you can potentially achieve a rounded balance by using differing kinds or types of sensors. Cameras and visual processing are usually not as adept at being indicative of the speed of an object as does the radar or the LIDAR. By exploiting the strengths of each kind of sensor, you are able to have a more enriched texturing of what the real-world consists of.

If the sensor fusion subsystem is poorly devised, it can undermine this complimentary triangulation that having differing kinds of sensors inherently provides. It’s a shame. Weak or slimly designed sensor fusion often tosses away important information that could be used to better gauge the surroundings. With a properly concocted complimentary perspective, the AI action planner portion has a greater shot at making better driving decisions because it is more informed about the real-world around the self-driving car.

Let’s though all acknowledge that the more processing you do of the multitude of sensors, the more computer processing you need, which then means that you have to place more computer processors and memory on-board the self-driving car. This adds cost, it adds weight to the car, it consumes electrical power, it generates heat, and has other downsides. Furthermore, trying to bring together all of the data and interpretations is going to take processing time, of which, as emphasized herein many times, the time constraints for the AI are quite severe when driving a car.

For my article about the cognition timing aspects of AI self-driving cars, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/cognitive-timing-for-ai-self-driving-cars/

For the aspects of LIDAR, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/lidar-secret-sauce-self-driving-cars/

For the use of compressive sensing, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/compressive-sensing-ai-self-driving-cars/

For my article about the safety of AI self-driving cars, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/safety-and-ai-self-driving-cars-world-safety-summit-on-autonomous-tech/

Four Key Ways Approaches to MSDF Assimilation

Let’s consider the fundamental ways that you assimilate together the sensory data from multiple sensors.

Take a look at Figure 2.

I’ll briefly describe the four approaches, consisting of harmonize, reconcile, integrate, and synthesize.

- Harmonize

Assume that you have two different kinds of sensors, I’ll call them sensor X and sensor Z. They each are able to sense the world outside of the self-driving car. We won’t concern ourselves for the moment with their respective strengths and weaknesses, which I’ll be covering later on herein.

There is an object in the real-world and the sensor X and the sensor Z are both able to detect the object. This could be a pedestrian in the street, or maybe a dog, or could be a car. In any case, I’m going to simplify the matter to considering the overall notion of detecting an object.

This dual detection means that both of the different kinds of sensors have something to report about the object. We have a dual detection of the object. Now, we want to figure out how much more we can discern about the object because we have two perspectives about it.

This involves harmonizing the two reported detections. Let’s pretend that both sensors detect the distance of the object. And, sensor X indicates the object is six feet tall and about two feet wide. Meanwhile, sensor Z is reporting that the object is moving toward the self-driving car, doing so at a speed of a certain number of feet per second N. We can combine together the two sensor reports and update the virtual world model that there is an object of six feet in height, two feet in width, moving toward the self-driving car at some speed N.

Suppose we only relied upon sensor X. Maybe because we only have sensor X and there is no sensor Z on this self-driving car. Or, sensor Z is broken. Or, sensor Z is temporarily out of commission because there is a bunch of mud sitting on top of the sensor. In this case, we would know only the height and weight and general position of the object, but not have a reading about its speed and direction of travel. That would mean that the AI action planner is not going to have as much a perspective on the object as might be desired.

As a quick aside, this also ties into ongoing debates about which sensors to have on AI self-driving cars. For example, one of the most acrimonious debates involves the choice by Tesla and Elon Musk to not put LIDAR onto the Tesla cars. Elon has stated that he doesn’t believe LIDAR is needed to achieve a true AI Level 5 self-driving car via his Autopilot system, though he also acknowledges that he might ultimately be proven mistaken by this assumption.

Some would claim that the sensory input available via LIDAR cannot be otherwise fully devised via the other kinds of sensors, and so in that sense the Teslas are not going to have the same kind of complimentary or triangulation available that self-driving cars with LIDAR have. Those that are not enamored of LIDAR would claim that the LIDAR sensory data is not worth the added cost, nor worth the added processing effort, nor worth the added cognition time required for processing.

I’ve pointed out that this is not merely a technical or technological question. It is my bet that once AI self-driving cars get into foul car accidents, we’ll see lawsuits that will attempt to go after the auto makers and tech firms for the sensory choices made in the designs of their AI self-driving cars.

If an auto maker or tech firm opted to not use LIDAR, a lawsuit might contend that the omission of LIDAR was a significant drawback to the capabilities of the AI self-driving car, and that the auto maker or tech firm knew or should have known that they were under-powering their AI self-driving car, making it less safe. This is going to be a somewhat “easier” claim to launch, especially due to the aspect that most AI self-driving cars are being equipped with LIDAR.

If an auto maker or tech firm opts to use LIDAR, a lawsuit might contend that the added effort by the AI system to process the LIDAR was a contributor to the car wreck, and that the auto maker or tech firm knew or should have known that the added processing and processing time could lead to the AI self-driving car being less safe. This claim will be more difficult to lodge and support, especially since it goes against the tide of most AI self-driving cars being equipped with LIDAR.

For the crossing of the Rubicon for these kinds of questions, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/crossing-the-rubicon-and-ai-self-driving-cars/

For the emergence of lawsuits about AI self-driving cars, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/first-salvo-class-action-lawsuits-defective-self-driving-cars/

For my article about other kinds of legal matters for AI self-driving cars, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/self-driving-car-lawsuits-bonanza-ahead/

For my Top 10 predictions about where AI self-driving cars are trending, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/top-10-ai-trends-insider-predictions-about-ai-and-ai-self-driving-cars-for-2019/

- Reconcile

I’d like to revisit the use of sensor X and sensor Z in terms of object detection.

Let’s pretend that sensor X detects an object, and yet sensor Z does not, even though the sensor Z could have. In other words, the object is within the Field of View (FOV) of sensor Z, and yet sensor Z isn’t detecting the object. Note that this is vastly different than if the object were entirely outside the FOV of sensor Z, in which case we would not have any expectation that sensor Z could detect the object.

We have a bit of a conundrum on our hands that needs reconciling.

Sensor X says the object is there in the FOV. Sensor Z says the object is not there in the same FOV intersection. Yikes! It could be that sensor X is correct and sensor Z is incorrect. Perhaps sensor Z is faulty, or obscured, or having some other difficulty. On the other hand, maybe sensor X is incorrect, namely that there isn’t an object there, and the sensor is X is mistaken, reporting a “ghost” of sorts, something that is not really there, while sensor Z is correct in reporting that there isn’t anything there.

There are various means to try and reconcile these seemingly contradictory reports. I’ll be getting to those methods shortly herein.

- Integrate

Let’s suppose we have two objects. One of those objects is in the FOV of sensor X. The other object is within the FOV of sensor Z. Sensor X is not able to directly detect the object that sensor Z has detected, rightfully so because the object is not inside the FOV of sensor X. Sensor Z is not able to directly detect the object that sensor X has detected, rightfully so because the object is not inside the FOV of sensor Z.

Everything is okay in that the sensor X and sensor Z are both working as expected.

What we would like to do is see if we can integrate together the reporting of sensor X and sensor Z. They each are finding objects in their respective FOV. It could be that the object in the FOV of sensor Z is heading toward the FOV of sensor X, and thus it might be possible to inform sensor X to especially be on the watch for the object. Likewise, the same could be said about the object that sensor X currently has detected and might forewarn sensor Z.

My story about driving in the fog is a similar example of integrating together sensory data. The cars seen by my front passenger and by those sitting in the backseat of my car were integrated into my own mental processing about the driving scene.

- Synthesize

In the fourth kind of approach about assimilating together the sensory data, you can have a situation whereby neither sensor X and nor sensor Z has an object within their respective FOV’s. In this case, the assumption would be that neither one even knows that the object exists.

In the case of my driving in the fog, suppose a bike rider was in my blind spot, and that neither of my buddies saw the bike rider due to the fog. None of us knew that a bike rider was nearby. We are all blind to the bike rider. There are likely going to be gaps in the FOV’s of the sensors on an AI self-driving car, which suggests that at times there will be parts or objects of the surrounding real-world that the AI action planner is not going to know is even there.

You sometimes have a chance at guessing about objects that aren’t in the FOV’s of the sensors by interpreting and interpolating whatever you do know about the objects within the FOV’s of the sensors. This is referred to as synthesis or synthesizing of sensor fusion.

Remember how I mentioned that I saw other cars moving over when I was hearing the sounds of a siren. I could not see the emergency vehicle. Luckily, I had a clue about the emergency vehicle because I could hear it. Erase the hearing aspects and pretend that all that you had was the visual indication that other cars were moving over to the side of the road.

Within your FOV, you have something happening that gives you a clue about what is not within your FOV. You are able to synthesize what you do know and use that to try and predict what you don’t know. It seems like a reasonable guess that if cars around you are pulling over, it suggests an emergency vehicle is coming. I guess it could mean that aliens from Mars have landed and you didn’t notice it because you were strictly looking at the other cars, but I doubt that possibility of those alien creatures landing here.

So, you can use the sensory data to try and indirectly figure out what might be happening in FOV’s that are outside of your purview. Keeping in mind that this is real-time system and that the self-driving car is in-motion, it could be that within moments the thing that you guessed might be in the outside of scope FOV will come within the scope of your FOV, and hopefully you’ll have gotten ready for it. Just as I did about the ambulance that zipped past me.

For my article about dealing with emergency vehicles, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/emergency-vehicle-awareness-self-driving-cars/

For the use of computational periscopy and shadow detection, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/ai-insider/computational-periscopy-and-ai-the-case-of-ai-self-driving-cars/

For the emergence of e-Nose sensors, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/olfactory-e-nose-sensors-and-ai-self-driving-cars/

For my article about fail-safe aspects of AI self-driving cars, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/fail-safe-ai-and-self-driving-cars/

Voting Methods of Multi-Sensor Data Fusion

When you have multiple sensors and you want to bring together in some cohesive manner their respective reporting, there are a variety of methods you can use.

Take a look at Figure 1 again.

I’ll briefly describe each of the voting methods.

- Absolute Ranking Method

In this method, you beforehand decide a ranking of sensors. You might declare that the cameras are higher ranked than the radar. The radar you might decide is higher ranked than the LIDAR. And so on. During sensor fusion, the subsystem uses that predetermined ranking.

For example, suppose you get into a situation of reconciliation, such as the instance I described earlier involving sensor X detecting an object in its FOV but that sensor Z in the intersecting FOV did not detect. If sensor X is the camera, while sensor Z is the LIDAR, you might simply use the pre-determined ranking and the algorithm assumes that since the camera is higher ranking it is “okay” that the sensor Z does not detect the object.

There are tradeoffs to this approach. It tends to be fast, easy to implement, and simple. Yet it tends toward doing the kind of “tossing out” that I forewarned is not usually advantageous overall.

- Circumstances Ranking Method

This is similar to the Absolute Ranking Method but differs because the ranking is changeable depending upon the circumstance in-hand. For example, we might have setup that if there is rainy weather, the camera is no longer the top dog and instead the radar gets the topmost ranking, due to its less likelihood of being adversely impacted by the rain.

There are tradeoffs to this approach too. It tends to be relatively fast, easy to implement, and simple. Yet it once again tends toward doing the kind of “tossing out” that I forewarned is not usually advantageous overall.

- Equal Votes (Consensus) Method

In this approach, you allow each sensor to have a vote. They are all considered equal in their voting capacity. You then use a counting algorithm that might go with a consensus vote. If some threshold of the sensors all agrees about an object, while some do not, you allow the consensus to decide what the AI system is going to be led to believe.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

- Weighted Voting (Predetermined)

Somewhat similar to the Equal Votes approach, this approach adds a twist and opts to assume that some of the voters are more important than the others. We might have a tendency to believe that the camera is more dependable than the radar, so we give the camera a higher weighted factor. And so on.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

- Probabilities Voting

You could introduce the use of probabilities into what the sensors are reporting. How certain is the sensor? It might have its own controlling subsystem that can ascertain whether the sensor has gotten bona fide readings or maybe has not been able to do so. The probabilities are then encompassed into the voting method of the multiple sensors.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

For more about probabilistic reasoning and AI self-driving cars, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/ai-insider/probabilistic-reasoning-ai-self-driving-cars/

- Arguing (Your Case) Method

A novel approach involves having each of the sensors argue for why their reporting is the appropriate one to use. It’s an intriguing notion. We’ll have to see whether this can demonstrate sufficient value to warrant being used actively. Research and experimentation are ongoing.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

For more about arguing machines as a method in AI, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/features/ai-arguing-machines-and-ai-self-driving-cars/

- First-to-Arrive Method

This approach involves declaring a kind of winner as to the first sensor that provides its reporting is the one that you’ll go with. The advantage is that for timing purposes, you presumably won’t wait for the other sensors to report, which then speeds up the sensor fusion effort. On the other hand, you don’t know if a split second later one of the other sensors might report something of a contrary nature or that might be an indication of imminent danger that the first sensor did not detect.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

- Most-Reliable Method

In this approach, you keep track of the reliability of the myriad of sensors on the self-driving car. The sensor that is most reliable will then get the nod when there is a sensor related data dispute.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

- Survivor Method

It could be that the AI self-driving car is having troubles with the sensors. Maybe the self-driving car is driving in a storm. Several of the sensors might not be doing any viable reporting. Or, perhaps the self-driving car has gotten sideswiped by another car, damaging many of the sensors. This approach involves selecting the sensors based on their survivorship.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

For my article about driving of AI self-driving cars in hurricanes and other natural disasters, see: https://www.aitrends.com/selfdrivingcars/hurricanes-and-ai-self-driving-cars-plus-other-natural-disasters/

For what happens when an AI self-driving car is involved in an accident, see my article: https://www.aitrends.com/ai-insider/accidents-happen-self-driving-cars/

- Random Selection (Worst Case)

One approach that is obviously controversial involves merely choosing among the sensor fusion choice by random selection, doing so if there seems to not be any other more systemic way to choose between multiple sensors if they are in disagreement about what they have or have not detected.

Like the other methods, there are tradeoffs in doing things this way.

- Other

You can use several of these methods in your sensor fusion subsystem. They can each come to play when the subsystem determines that one approach might be better than the other.

There are other ways that the sensor fusion voting can also be arranged.

How Multiple Sensors Differ is Quite Important

Your hearing is not the same as your vision. When I heard a siren, I was using one of my senses, my ears. They are unlike my eyes. My eyes cannot hear, at least I don’t believe they can. This highlights that there are going to be sensors of different kinds.

An overarching goal or structure of the Multi-Sensor Data Fusion involves trying to leverage the strengths of each sensor type, while also minimizing or mitigating the weaknesses of each type of sensor.

Take a look at Figure 3.

One significant characteristic of each type of sensor will be the distance at which it can potentially detect objects. This is one of the many crucial characteristics about sensors.

The further out that the sensor can detect, the more lead time and advantage goes to the AI driving task. Unfortunately, often the further reach also comes with caveats, such as the data at the far ends might be lackluster or suspect. The sensor fusion needs to be established as to the strengths and weaknesses based on the distances involved.

Here’s the typical distances for contemporary sensors, though keep in mind that daily improvements are being made in the sensor technology and these numbers are rapidly changing accordingly.

- Main Forward Camera: 150 m (about 492 feet) typically, condition dependent

- Wide Forward Camera: 60 m (about 197 feet) typically, condition dependent

- Narrow Forward Camera: 250 m (about 820 feet) typically, conditions dependent

- Forward Looking Side Camera: 80 m (about 262 feet) typically, condition dependent

- Rear View Camera: 50 m (about 164 feet) typically, condition dependent

- Rearward Looking Side Camera: 100 m (about 328 feet) typically, condition dependent

- Radar: 160 m (about 524 feet) typically, conditions dependent

- Ultrasonic: 8 m (about 26 feet) typically, condition dependent

- LIDAR: 200 m (about 656 feet) typically, condition dependent

There are a number of charts that attempt to depict the strengths and weaknesses when comparing the various sensor types. I suggest you interpret any such chart with a grain of salt. I’ve seen many such charts that made generalizations that are either untrue or at best misleading.

Also, the number of criteria that can be used to compare sensors is actually quite extensive, and yet the typical comparison chart only picks a few of the criteria. Once again, use caution in interpreting those kinds of short shrift charts.

Take a look at Figure 4 for an indication about the myriad of factors involved in comparing different types of sensors.

As shown, the list consists of:

- Object detection

- Object distinction

- Object classification

- Object shape

- Object edges

- Object speed

- Object direction

- Object granularity

- Maximum Range

- Close-in proximity

- Width of detection

- Speed of detection

- Nighttime impact

- Brightness impact

- Size of sensor

- Placement of sensor

- Cost of sensor

- Reliability of sensor

- Resiliency of sensor

- Snow impact

- Rain impact

- Fog impact

- Software for sensor

- Complexity of use

- Maintainability

- Repairability

- Replaceability

- Etc.

Conclusion

It seems that the sensors on AI self-driving cars get most of the glory in terms of technological ’wizardry and attention. The need for savvy and robust Multi-Sensor Data Fusion does not get much airplay. As I hope you have now discovered, there is an entire and complex effort involved in doing sensor fusion.

Humans appear to easily do sensor fusion. When you dig into the details of how we do so, there is a tremendous amount of cognitive effort involved. For AI self-driving cars, we need to continue to press forward on ways to further enhance Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. The future of AI self-driving cars and the safety of those that use them are dependent upon MSDF. That’s a fact.

Copyright 2019 Dr. Lance Eliot

This content is originally posted on AI Trends.

AI Recognition Software Making a Business of Your Face

Facial recognition software is a powerful technology that poses serious threats to civil liberties. It’s also a booming business. Today, dozens of startups and tech giants are selling face recognition services to hotels, retail stores—even schools and summer camps. The business is flourishing thanks to new algorithms that can identify people with far more precision than even five years ago. In order to improve these algorithms, companies trained them on billions of faces—often without asking anyone’s permission. Indeed, chances are good that your own face is part of a “training set” used by a facial recognition firm or part of a company’s customer database.

Consumers may be surprised at some of the tactics companies have used to harvest their faces. In at least three cases, for instance, firms have obtained millions of images by harvesting them via photo apps on people’s phones. For now, there are few legal restrictions on facial recognition software, meaning there is little people can do to stop companies using their face in this manner.

In 2018, a camera collected the faces of passengers as they hurried down an airport jetway near Washington, D.C. In reality, neither the jetway nor the passengers were real; the entire structure was merely a set for the National Institute for Science and Technology (NIST) to demonstrate how it could collect faces “in the wild.” The faces would become part of a recurring NIST competition that invites companies across the globe to test their facial recognition software.

In the jetway exercise, volunteers gave the agency consent to use their faces. This is how it worked in the early days of facial recognition; academic researchers took pains to get permission to include faces in their data sets. Today, companies are at the forefront of facial recognition, and they’re unlikely to ask for explicit consent to use someone’s face—if they bother with permission at all.

The companies, including industry leaders like Face++ and Kairos, are competing in a market for facial recognition software that is growing by 20% each year and is expected to be worth $9 billion a year by 2022, according to Market Research Future. Their business model involves licensing software to a growing body of customers—from law enforcement to retailers to high schools—which use it run facial recognition programs of their own.

In the race to produce the best software, the winners will be companies whose algorithms can identify faces with a high degree of accuracy without producing so-called false positives. As in other areas of artificial intelligence, creating the best facial recognition algorithm means amassing a big collection of data—faces, in this case—as a training tool. While companies are able to use the sanctioned collections compiled by government and universities, such as the Yale Face Database, these training sets are relatively small and contain no more than a few thousand faces.

These official data sets have other limitations. Many lack racial diversity or fail to depict conditions—such as shadows or hats or make-up—that can change how faces appear in the real world. In order to build facial recognition technology capable of spotting individuals “in the wild,” companies needed more images. Lots more.

“Hundreds are not enough, thousands are not enough. You need millions of images. If you don’t train the database with people with glasses or people of color, you won’t get accurate results,” says Peter Trepp, the CEO of FaceFirst, a California-based facial recognition company that helps retailers screen for criminals entering their stores.

Where might a company obtain millions of images to train its software? One source has been databases of police mug shots, which are publicly available from state agencies and are also for sale by private companies. California-based Vigilant Solutions, for instance, offers a collection of 15 million faces as part of its facial recognition “solution.”

Some startups, however, have found an even better source of faces: personal photo album apps. These apps, which compile photos stored on a person’s phone, typically contain multiple images of the same person in a wide variety of poses and situations—a rich source of training data.

“We have consumers who tag the same person in thousands of different scenarios. Standing in the shadows, with hats-on, you name it,” says Doug Aley, the CEO of Ever AI, a San Francisco facial recognition startup that launched in 2012 as EverRoll, an app to help consumers manage their bulging photo collections.

Read the source article in Fortune.

NYPD Tracks Crimes Across City with Its Own Pattern-Seeking AI Tool

The details of the crime were uniquely specific: Wielding a hypodermic syringe as a weapon, a man in New York City attempted to steal a power drill from a Home Depot in the Bronx. After police arrested him, they quickly ascertained that he’d done the same thing before, a few weeks earlier at another Home Depot, seven miles away in Manhattan.

It wasn’t a detective who linked the two crimes. It was a new technology called Patternizr, an algorithmic machine-learning software that sifts through police data to find patterns and connect similar crimes. Developed by the New York Police Department, Patternizr is the first tool of its kind in the nation (that we know about). It’s been in use by NYPD since December 2016, but its existence was first disclosed by the department this month.

“The goal of all of this is to identify patterns of crime,” says Alex Chohlis-Wood, the former director of analytics for NYPD and one of the researchers who worked on Patternizr. He is currently the deputy director of Stanford University’s Computational Policy Lab. “When we identify patterns more quickly, it helps us make arrests more quickly.”

Many privacy advocates, however, worry about the implications of deploying artificial intelligence to fight crimes, particularly the potential for it to reinforce existing racial and ethnic biases.

New York City has the largest police force in the country, with 77 precincts spread across five boroughs. The number of crime incidents is vast: In 2016, NYPD reported more than 13,000 burglaries, 15,000 robberies and 44,000 grand larcenies. Manually combing through arrest reports is laborious and time-consuming — and often fruitless.

“It’s difficult to identify patterns that happen across precinct boundaries or across boroughs,” says Evan Levine, NYPD’s assistant commissioner of data analytics.

Patternizr automates much of that process. The algorithm scours all reports within NYPD’s database, looking at certain aspects — such as method of entry, weapons used and the distance between incidents — and then ranks them with a similarity score. A human data analyst then determines which complaints should be grouped together and presents those to detectives to help winnow their investigations.

On average, more than 600 complaints per week are run through Patternizr. The program is not designed to track certain crimes, including rapes and homicides. In the short term, the department is using the technology to track petty larcenies.

The NYPD used 10 years of manually collected historical crime data to develop Patternizr and teach it to detect patterns. In 2017, the department hired 100 civilian analysts to use the software. While the technology was developed in-house, the software is not proprietary, and because the NYPD published the algorithm, “other police departments could take the information we’ve laid out and build their own tailored version of Patternizr,” says Levine.

Since the existence of the software was made public, some civil liberties advocates have voiced concerns that a machine-based tool may unintentionally reinforce biases in policing.

“The institution of policing in America is systemically biased against communities of color,” New York Civil Liberties Union legal director Christopher Dunn told Fast Company. “Any predictive policing platform runs the risks of perpetuating disparities because of the over-policing of communities of color that will inform their inputs. To ensure fairness, the NYPD should be transparent about the technologies it deploys and allow independent researchers to audit these systems before they are tested on New Yorkers.”

New York police point out that the software was designed to exclude race and gender from its algorithm. Based on internal testing, the NYPD told Fast Company, the software is no more likely to generate links to crimes committed by persons of a specific race than a random sampling of police reports.

Read the source article in Governing.

UK’s NHS Thinking Through Role of AI in Medical Decision-Making

In many areas of industry and research, people are excited about artificial intelligence (AI). Nowhere more so than in medicine, where AI promises to make clinical care better, faster and cheaper.

Last year, UK Prime Minister Theresa May said that “new technologies are making care safer, faster and more accurate, and enabling much earlier diagnosis”.

Backing developments in medical AI is seen in the UK as an important step in improving the provision of care for the National Health Service (NHS) – the UK Government recently launched a “Grand Challenge” focusing on the power of AI to accelerate medical research and lead to better diagnosis, prevention and treatment of diseases.

With companies and research institutions announcing that AI systems can outperform doctors in diagnosing heart disease, detecting skin cancer and carrying out surgery, it’s easy to see why the idea of “Dr Robot” coming in to revolutionize healthcare and save cash-strapped public healthcare is so attractive.

But as AI-enabled medical tools are developed and take over aspects of healthcare, the question of medical liability will need to be addressed.

Whose fault is it?

When the outcome of medical treatment is not what was hoped for, as inevitably is the case for some patients, the issue of medical negligence sometimes come into play. When things go wrong, patients or their loved ones may want to know whether it was anyone’s fault.

Medical negligence in the UK is a well-established area of law which seeks to balance the patient’s expectations of proper care with the need to protect doctors who have acted competently but were not able to achieve a positive outcome. Generally, doctors will not be held to have been negligent if they followed accepted medical practice.

The UK’s General Medical Council guidelines say that doctors can delegate patient care to a colleague if they are satisfied that the colleague has sufficient knowledge, skills and experience to provide the treatment, but responsibility for the overall care of the patient remains with the delegating doctor.

Similarly, a surgeon using a robotic surgery tool would remain responsible for the patient, even if the robot was fully autonomous. But what if, unbeknownst to the surgeon, there was a bug in the robot’s underlying code? Would it be fair to blame the surgeon or should the fault lie with the robot’s manufacturer?

Currently, many of the AI medical solutions being developed are not intended to be autonomous. They are made as a tool for medical professionals, to be used in their work to improve efficiency and patient outcomes. In this, they are like any other medical tool already used – no different, for example, to an MRI scanner.

If a tool malfunctions, the clinician could still be at risk of a medical negligence claim, though the hospital or the practitioner could then mount a separate action against the product manufacturer. This remains the same for AI products, but as they acquire more autonomy new questions on liability will arise.

The use of AI decision-making solutions could lead to a “black box” problem: although the input data and the output decision are known, the exact steps taken by the software to reach the decision from the data cannot always be retraced. If the outcome decision is wrong, it may be impossible to reconstruct the reason the software reached a particular outcome.

In a situation where an AI device matches or outperforms a medical professional on a certain medical problem, the device would statistically be providing better care if, on average (and with statistical significance), patients were receiving better outcomes by being visited by “Dr Robot” rather than “Dr Human”.

Though Dr Robot could perform better overall, for example by diagnosing correctly 98 per cent of the time as compared to Dr Human’s success rate of 95 per cent, there may be a small number of edge cases for which Dr Robot reaches the wrong outcome, but where the right outcome would be obvious to a doctor. Legally, medical negligence arises if a doctor fails to do what a reasonable doctor would have done.

If the autonomous AI system reaches a decision that no reasonable doctor would have reached, the individual patient would have grounds to claim for medical negligence even if, overall, across all patients, the AI system is reaching better outcomes.

The question for the misdiagnosed patient will be: who should I sue?

Innovative solutions

One answer to this could be new insurance models for AI tools. Last year, the US gave the first ever medical regulatory approval to an autonomous AI device to the IDx-DR retinal scanner. This tool operates independently, without the oversight of a medical professional, to assess whether a patient needs to be referred to a doctor.

The tool’s developers, IDx, have medical negligence insurance to protect the company against liability issues, and specialist AI insurance packages have sprung up to cater for this developing need.

Rather than every medical tool having its own insurance, the idea of governmental solution has also been proposed. An organization could assess the risk of each AI product and allow the developer of the product to commercialize it in return for paying the appropriate “risk fee” to the regulator.

The fee would then fund a pool for pay-outs in case of AI malfunction. This solution, sometimes called a Turing Registry (or EU Agency for Robotics and Artificial Intelligence, as proposed by the European Parliament) would get round the “black box” problem, as the registry would pay out on claims involving a registry-certified AI product, without having to determine the underlying cause of the problem.

Read the source article in The Telegraph.

SC postpones crypto ban case hearing to July

Second-biggest crypto coin loses mojo as apps move elsewhere

MLflow v0.9.0 Features SQL Backend, Projects in Docker, and Customization in Python Models

MLflow v0.9.0 was released today. It introduces a set of new features and community contributions, including SQL store for tracking server, support for MLflow projects in Docker containers, and simple customization in Python models. Additionally, this release adds a plugin scheme to customize MLflow backend store for tracking and artifacts.

Now available on PyPI and with docs online, you can install this new release with pip install mlflow as described in the MLflow quickstart guide.

In this post, we will elaborate on a set of MLflow v0.9.0 features:

- An efficient SQL compatible backend store for tracking scales experiments in the thousands.

- A plugin scheme for tracking artifacts extends backend store capabilities.

- Ability to run MLflow projects in Docker Containers allows extensibility and stronger isolation during execution.

- Ability to customize Python models injects post and preprocessing logic in a python_func model flavor.

SQL Backend Store for Tracking

For thousands of MLflow runs and experimental parameters, the default File store tracking server implementation does not scale. Thanks to the community contributions from Anderson Reyes, the SQLAlchemy store, an open-source SQL compatible store for Python, addresses this problem, providing scalable and performant store. Compatible with other SQL stores (such as MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQLite, and MS SQL), developers can connect to a local or remote store for persisting their experimental runs, parameters, and artifacts.

Logging Runtimes Performance

We compared the logging performance of MySQL-based SqlAlchemyStore against FileStore. The setup involved 1000 runs spread over five experiments running on a MacBook Pro with four cores on Intel i7 and 16GB of memory. (In a future blog, we plan to run this benchmark on a large EC2 machine expecting even better performance.)

Measuring logging performance averaging over thousands of operations, we saw about 3X speed-up when using a database-backed store, as shown in Fig.1.

Furthermore, we stress-tested with multiple clients scaling up to 10 concurrent clients logging metrics, params, and tags to the backend store. While both stores show a linear increase in runtimes per operation, the database-backed store continued to scale with large concurrent loads.

Fig.1 Logging Performance Runtimes

Search Runtime Performance

Performance of Search and Get APIs showed a significant performance boost. The following comparison shows search runtimes for the two store types over an increasing number of runs.

Fig.2 Search Runtime Performance

For more information about backend store setup and configuration, read the documentation on Tracking Storage.

Customized Plugins for Backend Store

Even though the internal MLflow pluggable architecture enables different backends for both tracking and artifact stores, it does not provide an ability to add new providers to plug in handlers for new backends.

A proposal for MLflow Plugin System from the community contributors Andrew Crozier and Víctor Zabalza now enables you to register your store handlers with MLflow. This scheme is useful for a few reasons:

- Allows external contributors to package and publish their customized handlers

- Extends tracking capabilities and integration with stores available on other cloud platforms

- Provides an ability to provide a separate plugin for tracking and artifacts if desired

Central to this pluggable scheme is the notion of entrypoints, used effectively in other Python packages, for example, pytest, papermill, click etc. To integrate and provide your MLflow plugin handlers, say for tracking and artifacts, you will need to two class implementations: TrackingStoreRegistery and ArtifactStoreRegistery.

For a detail explanation on how to implement, register, and use this pluggable scheme for customizing backend store, read the proposal and its implementation details.

Projects in Docker Containers

Besides running MLflow projects within a Conda environment, with the help of community contributor Marcus Rehm, this release extends your ability to run MLflow projects within a Docker container. It has three advantages. First, it allows you to capture non-Python dependencies such as Java libraries. Second, it offers stronger isolation while running MLflow projects. And third, it opens avenues for future capabilities to add tools to MLflow for running other dockerized projects, for example, on Kubernetes clusters for scaling.

To run MLflow projects within Docker containers, you need two artifacts: Dockerfile and MLProject file. The Docker file expresses your dependencies how to build a Docker image, while the MLProject file specifies the Docker image name to use, the entry points, and default parameters to your model.

With two simple commands, you can run your MLflow project in a Docker container and view the runs’ results, as shown in the animation below. Take note that environment variable such as MLFLOW_TRACKING_URI is preserved in the container, so you can view its runs’ metrics in the MLflow UI.

docker build . -t mlflow-docker-examplemlflow run . -P alpha=0.5

Simple Python Model Customization

Often, ML developers want to build and deploy models that include custom inference logic (e.g., preprocessing, postprocessing or business logic) and data dependencies. Now you can create custom Python models using new MLflow model APIs.

To build a custom Python model, extend the mlflow.pyfunc.PythonModel class:

class PythonModel:

def load_context(self, context):

# context contains path files to the artifacts

def predict(self, context, input_df):

# your custom inference logic here

The load_context() method is used to load any artifacts (including other models!) that your model may need in order to make predictions. You define your model’s inference logic by overriding the predict() method.

The new custom models documentation demonstrates how PythonModel can be used to save XGBoost models with MLflow; check out the XGBoost example!

import mlflow.pyfunc

# Define the model class

class AddVal(mlflow.pyfunc.PythonModel):

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

def predict(self, context, model_input):

return model_input.apply(lambda column: column + self.val)

# Construct and save the model

model_path = "add_val_model"

add5_model = AddVal(val=5)

#save the model

mlflow.pyfunc.save_model(dst_path=model_path, python_model=add5_model)

For more information about the new model customization features in MLflow, read the documentation on customized Python models.

Other Features and Bug Fixes

In addition to these features, several other new pieces of functionality are included in this release. Some items worthy of note are:

Features

- [CLI] Add CLI commands for runs: now you can list, delete, restore, and describe runs through the CLI (#720, @DorIndivo)

- [CLI] The run command now can take